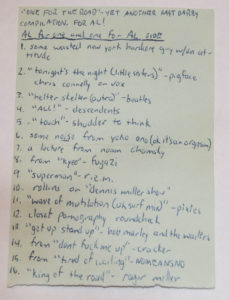

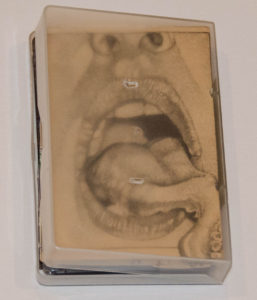

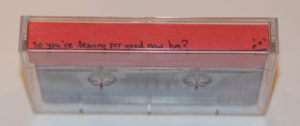

Remember that one mixtape you received that changed everything for you? The one that introduced you to the record labels, bands, scenes, and songs that would expand your influences further than you could have dreamed? Okay, now imagine that mixtape coming to you in video form. And you receive a new one every Saturday night at midnight. A charismatic funny-man called “Host” tells you about the videos. You go to the mall to buy tapes of the music you love from the videos, and sometimes they are available, but usually not. This is before the Internet, so you think you are at a loss. Then “Host” extends another hand: now you can buy the music you loved directly from him. You’re set.

Jeff Moody, “Host,” feels like an old friend of the family, though I only met him last year. Every Saturday night of my high school tenure, my sister Alison and I would eagerly prepare a VHS tape in the VCR in the living room of our home and tape Noise Network, a music video show out of Kenosha, WI. “Host,” as he was identified, would introduce the songs with gregarious humor. He talked to us like we were already in on what was cool. He was like having a fun, unpretentious, well-read older brother who didn’t mind telling the kids about what they yearned to understand and didn’t know how to ask about.

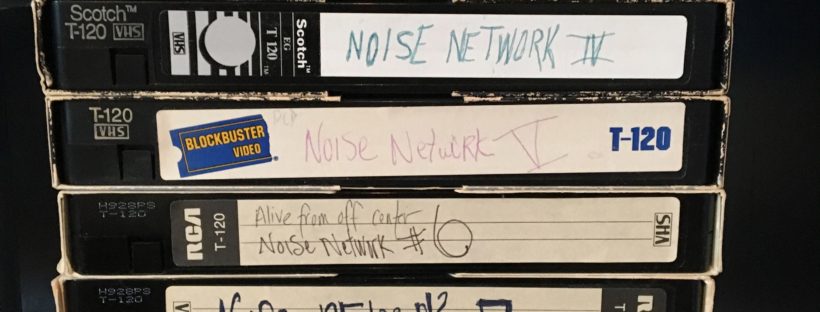

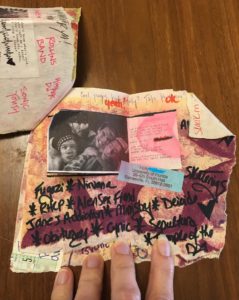

My sister Alison and I taped every episode. We painstakingly created indexes with VHS tracking times noted for each video. We rewatched our favorites. When Alison moved away after high school, I made a vhs mix for her with her favorite Noise Network videos to remind her of home.

stack of Noise Network/ Noise Bazaar VHS tapes

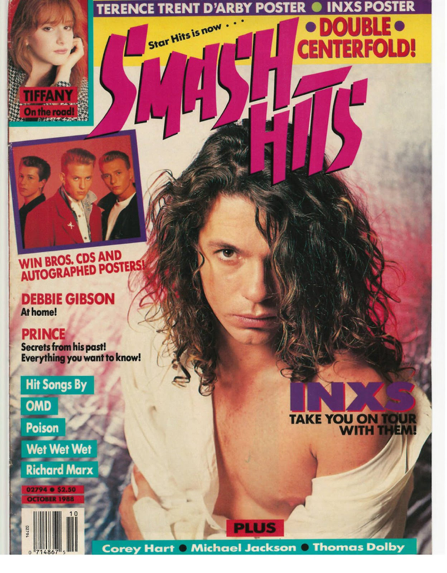

We had been jealous of our friends who had cable and let us watch their vhs tapes of 120 Minutes. But here I was, braces just off, contact lenses finally replacing the glasses I never wore, home from one of my first fumbling, exciting teenage romantic nights out, unwittingly stumbling upon the best underground music education I could ever hope for. Alison and I thought our prayers had been answered. They had.

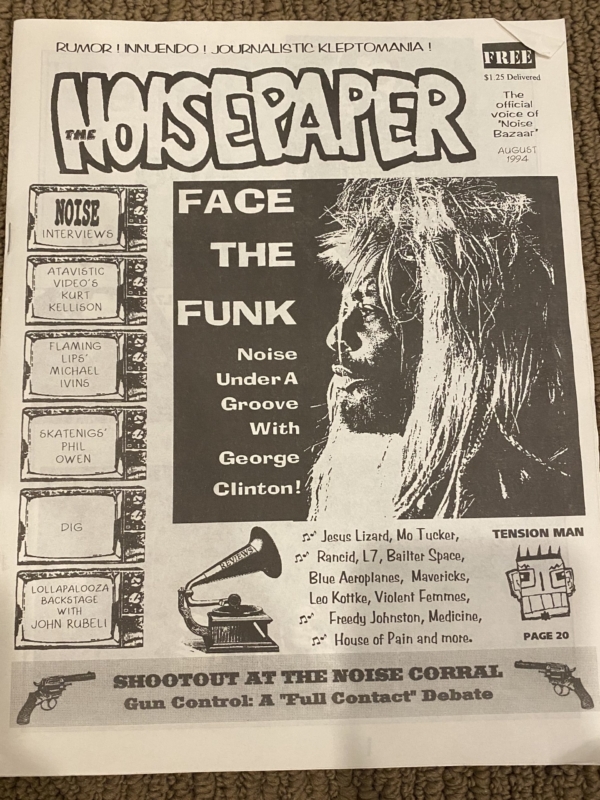

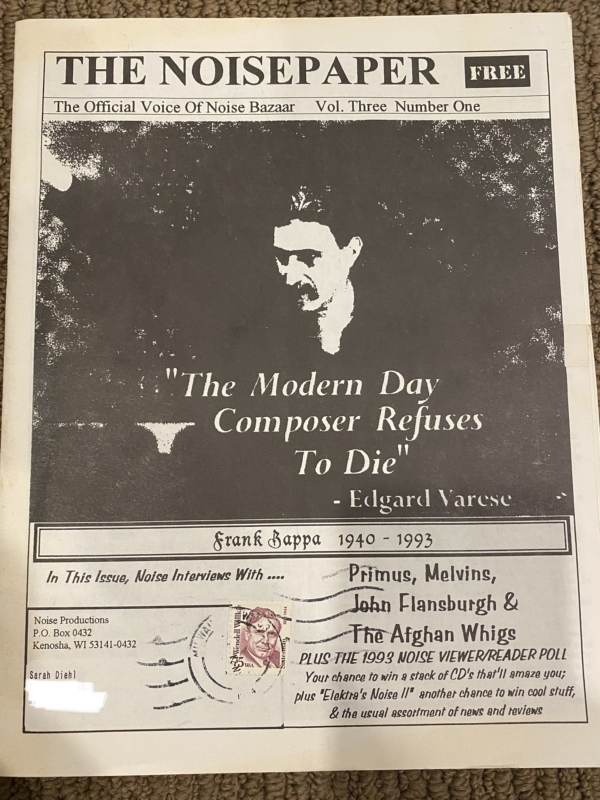

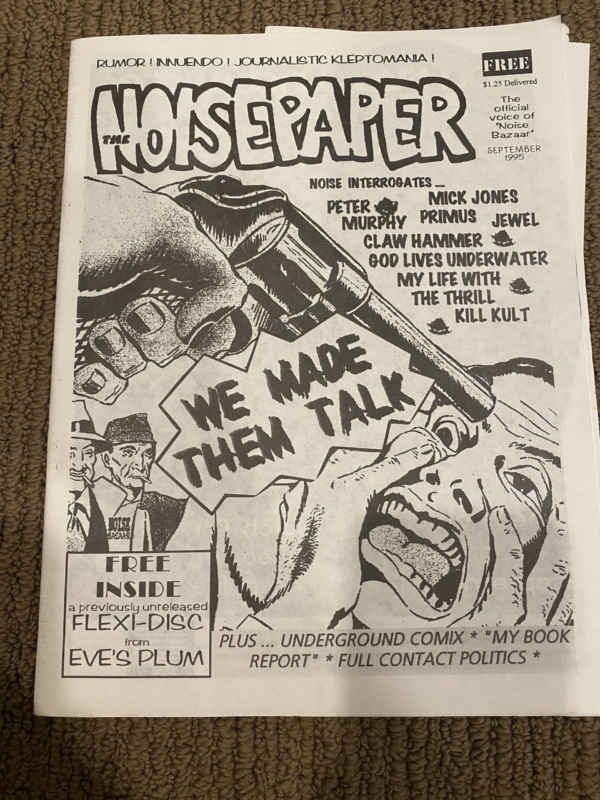

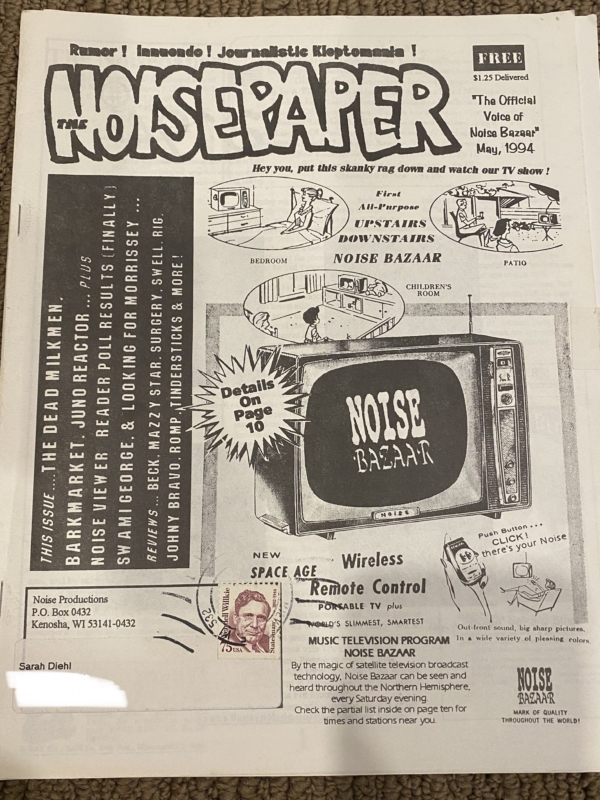

When I met Jeff Moody for this interview, at PRF Thundersnow in Escanaba MI in 2019 https://www.prfbbq.com/category/event/prf-thundersnow-2019, he spent a large part of the time before, during, and after the event talking excitedly about other people’s bands, podcasts, and projects. He is an inveterate champion of others. Ironically, most of the people at PRF Thundersnow did not know that Jeff spent 7 years hosting an underground music video program and music home shopping program long before the Internet, a program that also produced a zine called NoisePaper that was shipped to viewers’ doors— a project that influenced scores of people in towns and cities dotting the U.S. and even sparked a local music scene in Trinidad.

Here is the story of Noise Network and Noise Bazaar. Take it away, Jeff!…

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sarah: What were you doing when the Noise idea came about? Where were you in life?

Jeff: We were in college. And Noise Bazaar actually came out of a thing called Video Whiplash. Video Whiplash went to community colleges. I was taking classes in a radio broadcast communications program. I was programming the student radio station there. Frank Booth was the Instructional Media Coordinator there at the community college. He was hearing what I was doing with the radio station. I had changed everything that was going on with the radio station. And he got excited about it. Part of his thing with being Instructional Media Coordinator was to prepare educational programming for people over cable television. It was like Internet courses, but before the Internet. It was on direct cable television. People subscribed to a class, and they’d take their class at home over television.

Sarah: For college credit? Really?

Jeff: Yeah, that was his thing. So he was like, “You guys are doing really cool things with the radio station. How would you like to do a video show, too? Could you do it? I’d be interested in helping to put that together.”

He had all the technical skill. I’m all about aesthetics and nonsense, and he can actually pull things together. So we’re a pretty good team.

So we were doing Video Whiplash with some of the other students who were friends. And then after doing Video Whiplash for a while, it was pretty popular in town, and we were pretty focused on, “Why don’t we try to do one outside of town? And one that’s not tied to the school so we can do what we want.” Some of the videos that we were showing on Video Whiplash– because we always liked to push the envelope in terms of content–they were kind of like, “We got some calls about this. We got some calls about that.” So we were like, “Let’s try to do something on our own outside of the school.” And that’s where the idea came from.

Sarah: Okay. What school was this?

Jeff: Gateway Technical College in Kenosha.

from kenoshacounty.org

Sarah: You were a student at that school?

Jeff: I was a student there, yeah. Not a very good student. Not very far through. See, here’s how the college radio station there used to work. They didn’t really broadcast. They had a cable channel that the school had for their educational programming. When the educational programming wasn’t running, they would run audio from the student radio station. The student radio station would have a bake sale or a book sale twice a year to raise money. And then they would send the Program Director to the local record store, and they would buy like the top 40 45s, and then that’s what they would play for the next six months.

And my idea was, “There’s College Music Journal out there. And I think I can get a free subscription to College Music Journal if I report back to them what I was playing on the station. And if I can do that, then I can get record companies to just send us records. And the money that you are using to buy records through your bake sales or book sales or whatever—we can use that to buy new equipment.” That was my idea, to be Program Director for the station.

So everybody was kind of like, “Okay that sounds like a good idea.”

So I got a hold of CMJ. CMJ was like, “Yeah sure. Send us a playlist.” I started calling up record companies. Said, “We’re in CMJ.” I started with the big labels because they obviously have the most discretionary money. They’ll just throw you any records. It was the smaller labels that were tough to get. A really good example of that is Gerard Cosloy. Does that name ring a bell?

Sarah: Yes, Matador?

Jeff: Yeah. So before he was with Matador, Cosloy was with Homestead Records. And he was basically doing everything there. And one of the greatest features of College Music Journal was the letters section. Cosloy ruled the letters section. Somebody should take all of his CMJ letters and put them in a compendium book because his writing was brilliant. He was super funny. Super dead on. Ferocious about independent music and keeping the corporate labels out of it. He was one of the first guys I had an eye on, because I really liked him. I really wanted to get Homestead Records because I wanted to work with him. And his first response was, “Well, you’re playing the Screaming Blue Messiahs and you’re playing all this crap from Elektra and WEA and all the majors. Why am I going to send you my records?”

And his first response was, “Well, you’re playing the Screaming Blue Messiahs and you’re playing all this crap from Elektra and WEA and all the majors. Why am I going to send you my records?”

“I can’t play them if I don’t have them. I’m playing what I have right now. I’m just starting this thing out. So I know how it looks to you probably. But the goal is to get you and every other indie label in here, too, so we can really start working that. But right now I’ve got the majors sending me stuff because they can.”

He was kind of like, “Whatever…” And I kept at him and I kept at him. After about four or five months, he started seeing the playlists from CMJ and then he called me up one time. He said, “I’m glad you stayed on me because it looks like you’ve got a pretty cool thing going there.” He also saw that we were doing Video Whiplash, which is an extra thing that most college stations don’t do. We were one of the few college radio stations that actually had a video show too that was doing well. So he ended up sending me videos, too. And it was cool.

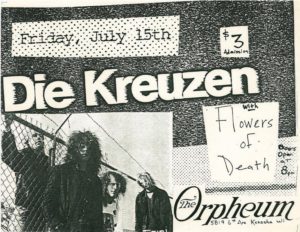

And I ended up booking shows in our town. One of our classmates who’s still one of my best friends, he was renovating a theatre in Kenosha, The Orpheum Theatre, and he wanted to have live music there.

built in 1922, the kenosha orpheum. photo from kenoshaorpheum.com

We had an early version of Smashing Pumpkins. We had Royal Crescent Mob from Ohio. My Dad Is Dead, who were on Homestead.

flyer for a die kreuzen show at the orpheum that jeff organized. he found this image online a while back and said, “that looks familiar!”

So the whole thing with Cosloy and a lot of other people, too. It sort of just developed into doing other things, too, like actually bringing bands in town.

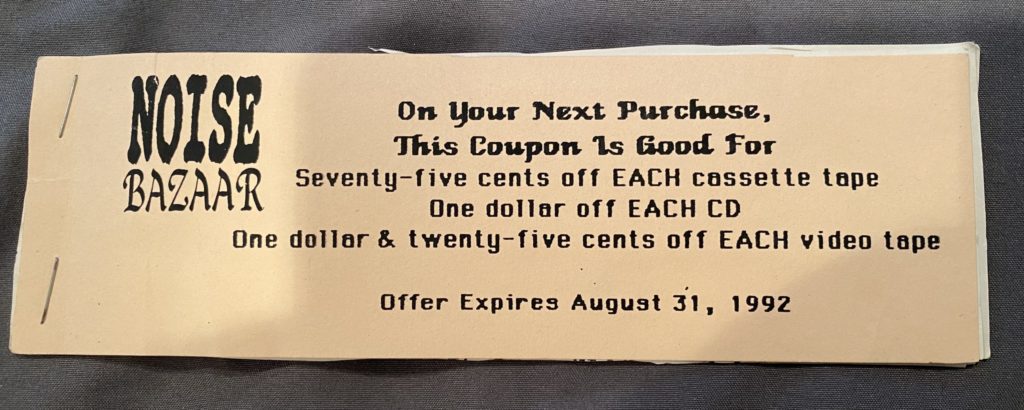

And we started doing Noise Network. At first, we were just a straight up music video show. And we knew we couldn’t get advertising in the traditional sense. So that’s when we started talking about how maybe we could supplement our advertising with selling records, because that seemed to be what people needed. That was the response we were getting from kids. The low power television network that we were talking about earlier, they were in towns like this! Escanaba would be a place for an LPTV station. Where are you going to go to the mall to a record shop to buy records up here—even back when there were record stores?! You’d have to go to Marquette, probably. That was the predicament a lot of kids were in. We filled that niche for selling records. But anyway, that’s how it started.

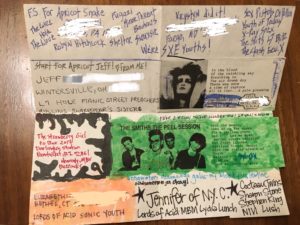

noise bazaar coupon – 75¢ off!

Sarah: So you had Video Whiplash. How did it progress from there to Noise?

Jeff: Video Whiplash was a college, noncommercial, nonprofit thing. We were trying to position Noise Bazaar as something that was going to make enough money to continue to fund itself instead of using school funds. Plus, we would have total creative control, too.

I think Revolting Cocks gave us problems just because of the name. We wanted to play Revolting Cocks all the time, everything that they had. Even if the song was clean and the video was clean, people would see the name and they’d call the school, “Hey! What’s this?” The school being a school, they were very smaller town, very reactionary. “Hey, you guys, what are you doing?” And they’d put some pressure on Frank, put some pressure on us. And that was when we started talking about, “Let’s try to do something on our own, just to see if we can do it!” And we ended up doing that for seven years.

Sarah: When you started it, did you have a sense of how long—did you have a vision of, “O gosh maybe this could expand outside of a certain area,” or?

Jeff: Of course, there was always the joke about how we’d eventually be able to just program shows from the beach. Just imagining. This was way before the Internet, way before wireless.

At the time, we had no idea what it was going to do, if anything. But the plan was to beat MTV. Or just be something cooler than MTV because you look at MTV now, over time, and it’s, “Yeah it was a cool thing that they were doing.” But the music programming that they were doing was pretty unadventurous. Even 120 Minutes, it was a lot of the stuff Cosloy was critical of, it was a lot of major label stuff. Homestead would never have anything on 120 Minutes. And Matt Pinfield might have been super stoked about something like Phantom Tollbooth that he might have seen on a small, small label, but for whatever reason, he was never able to get that stuff on. So that was our thing, to be something cooler than they were, just by virtue of playing stuff that no one would ever have a chance to hear.

We even took videos from bands that didn’t even have a record deal, but made a video themselves- or tried to. As long as it was weird and different, we would play it if we could. As long as it wasn’t nudity or violence that the FCC wouldn’t let us broadcast.

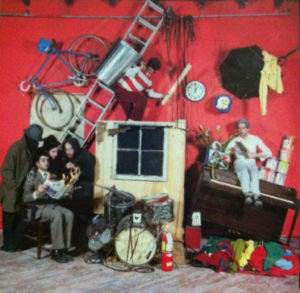

i loved this humidifier video. shot on super 8 = homemade necessarily?

Sarah: So, you had Video Whiplash. It turned into Noise. Video Whiplash had this college support, and then when you segued it to Noise, how were you accessing distribution?

Jeff: Even before that, when we did Video Whiplash, we were able to use the school’s equipment, so production-wise, everything was done at the school. Once we were done with that, and we were doing Noise, we worked out of this place called Jones Intercable in Kenosha.

Sarah: O! Yeah! I remember that in the credits!

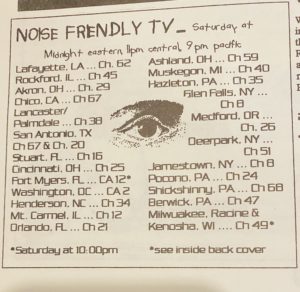

Jeff: Yeah, it was Jones Intercable. They were the local cable company. And they access television equipment. But we weren’t part of the whole access thing because we wanted to be a noncommercial thing. So they worked it out with us where – I don’t think they even charged us anything- maybe it was like 5 bucks a week- because the guy who was the station manager or the operations manager there, he liked us a lot. He wanted to see it happen. So he gave us kind of a sweet deal. At the time, it was me and Frank, and it was two other people, too, that were students. And then after [the first year] it was just Frank and me. Frank and I were pretty strident about what we wanted to do and the music that we wanted to play. At first, we were on a local cable channel in Kenosha, we had one in Racine, and we were on a local broadcast cable channel in Milwaukee. It was TV49 or something like that. They were like a weird UHF channel, and they picked up the show. I think that’s all we had until Channel America came along. And Channel America came along almost instantly, right at the right time.

Sarah: So what was Channel America?

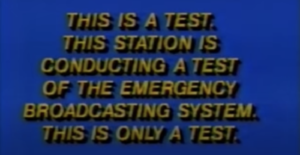

Jeff: They were a television network that catered to low power television stations. Low power television stations were government-owned broadcast stations that were set up for the Emergency Broadcast system. This is all before the Internet. It really was broadcast, right? So whenever there would be a tornado warning or something like that, these tv stations would put out a warning and hope that people would be watching that tv channel at the time so they’d be warned. [laughter] Weird, I guess. When you think about technology NOW and how you get these alerts on your phone, it’s so much more efficient than what they were trying to do back then. But they were trying to do it with the technology that they had.

People that owned these low powered tv stations were typically like, dentists or whatever. That was always the joke. It was someone who did good on their tax return and wanted to do a little something with their money, put it in something, so they’d buy a tv station. What are you going to put on your tv station? That’s where they came up with the idea of Channel America. You can provide really rock bottom, cheap programming. That was us!

It was funny because we would watch the satellite feed sometimes. So we would see what was on before us. And there was a tv show called “Only the Rich Cry” and it was one of those telenova things. It was hilarious! It was so terrible! It was like the worst soap opera! It was so bad it was hilarious. So we would try to tune into that before our show. We came on right after that.

That’s what Channel America was. The guy who was their program director was a guy who was a promotion person, a rep at a label. And he left that job to become program director. He called us up and said, “Your show’s perfect for this weird new network that I’m going to be working on. Do you want in?” And we were like, “Yeah definitely! We’ve got nothing else.” It was really good timing. And that got us on about 150 stations around the U.S. and Canada and then Trinidad, too.

Trinidad turned out to be a really huge thing for us because nobody in Trinidad had heard this music before. They had never heard the Cows or any of the Am Rep stuff. By all accounts, from all the mail we got from them- and years later I heard from a bunch of the people down there, too- I’m still in touch with some of them over social media—we really changed a lot of people’s lives down there. They heard this stuff and went nuts and started bands and started new music nights at clubs. They started a record store in Port-Au-Prince that catered to “alternative” music.

That’s how Channel America got going and pulled us in.

Sarah: Was that a business deal where you had a contract with Channel America?

Jeff: I don’t even think we signed anything. This guy loved the show. He must have been with a label that we liked a lot, a smaller label, an indie label. We must have liked him a lot because we did play a bunch of his stuff, and that’s how that relationship kind of went. He dug what we were doing, and they were our vehicle for a long time.

They even ran re-runs for a few years. I think they just went back to the first season and kept running it. I kept hearing from people- why are there re-runs? Well, because we quit. We’re not doing it anymore. “O that sucks.” Yep.

Sarah: So were you getting a lot of mail from the beginning?

Jeff: Ummmm, no. It just sort of progressed. In the beginning, we weren’t on too many stations. But once we got on Channel America, we started getting letters from all over the place. It was weird how many prisoners we got mail from. [laughter] Like in California, I remember specifically, there were a lot of guys who would write us, like “Yeah, I’m in for this amount of time. I always liked punk rock. You guys are cool. Thank god, it’s something weird and different in my life. I really look forward to your show every Saturday.” Yeah, a lot of prisoners in California for some reason. There must have been a couple of different prisons that let the guys watch the show. [laughter]

And then I remember the big places were Havasu City in Arizona. A weird little town. Got a lot of mail from Pittsburgh on a regular basis for a long time. Different cities in Ohio, Georgia, Texas—Plano, Texas, we had a station down there. When Trinidad hit, that’s when the letters doubled. For quite a while, half the mail was from everywhere else and then half the mail was coming from people in Trinidad who were like, “What is this?!”

Sarah: Would you answer the mail, at the time?

Jeff: We would pick a letter every week: “And now a letter from a viewer!”

There was this mystery for a while. Somebody was watching us on satellite. And they’d send us a postcard every month or so. And it would be from a different place. And it was always some kind of weird cryptic—Easter Island, or – it was all these really weird places. And they’d send a postcard that just had a pagan thing on it or something. And we were like, “Who’s this mystery person? This is so weird.” And we were never able to figure out who it was or where they actually lived or anything. But we always knew it was the same person because it had the same handwriting and it would always come from some strange place like the North Pole or somewhere way up in Canada that barely has a postal code. Very strange.

Yeah, the mail was really weird. And again, it was all before the Internet, so it was all snail mail. The Internet started coming around with email in like ‘94 or ‘95, so Frank had compuserv. So we had an email address but nobody knew how to use email at the time so we didn’t really get any email. We tried to set up an ordering service for records on the email. But again it was just too early for people to think about. It’s funny now! Everything’s done on the Internet. At the time, you couldn’t even get people to use fucking email. [laughter] It’s just weird.

Sarah: Tell me about getting content for the show.

noise bazaar is what made it possible for a 15-year old in a small town to wear a pylon t-shirt to school. and perpetuate this ‘tude.

Jeff: It’s kind of like when I was telling you about Cosloy. He was an early guy. A lot of what we were getting for Noise just was a natural progression from what I was doing at the college station. People knew me by then and so it was just really easy—and the more we worked at it, the easier it became. People started just sending us stuff. We didn’t even have to call and people were sending us stuff we didn’t even want. And it was all FedEx and UPS. Now everything is EPK [Electronic Press Kit] and you can send it electronically. But at the time, the amount of money that they were spending on overnighting videos! I would get 40-50 FedExes a week. My basement was just full of content. And they were sending them on ¾ inch tapes. So that’s huge. The difference now between all the physical stuff we had. You could fill a landfill with it. Versus EPKs, and just sending everything electronically. It’s totally different.

3/4″ tape. photo from currentpixel.com

But we just had such a reputation from the school days that it all carried over into Noise that it just got bigger and pretty soon everyone was sending us stuff.

One of the funniest stories—you know the song that’s on every football game- “Whoomp there it is! Whoomp there it is!” I can’t remember what the name of the group was but they were one of these Miami outfits. Luther Campbell was sending us stuff for a while. We got that video, and we were like, “This is the dumbest fucking thing I’ve ever seen in my life.” You know? “We’re not going to play this.” I think we did play it once at the end of a show with the end credits, because it was kind of fun but we were like, “This is so dumb.” Six months later, every football stadium, every place in the country is: “Whoomp there it is!” And we were like, “Yeah, we’re really good at picking what people want to hear, right? What are we doing, even?”

Sarah: What was that curation process like? You’re getting all this stuff.

Jeff: Every week, we would sit—when we first started, like I said, there were four of us, and I guess Frank and I got real nazi about things because there was stuff we definitely did want to play and there was stuff we definitely weren’t going to play. The other people involved- I think eventually we just wore them down. Then it just became him and me. Our vision- the two of us- was completely congruent. We both liked the same stuff, so it was really easy. A little different. I would turn Frank on to things, and he would open my mind to things: “Give it another try and think about this.” We both did that for years with each other.

Sarah: What was his aesthetic versus your aesthetic do you think?

Jeff: He got me into Nick Cave. He got me into Birthday Party. I think I got him into stuff he never really thought about like things that were newer coming up that he didn’t really hear.

I was always looking for – who haven’t I heard of yet that’s going to be great? Who’s going to be new? Guided By Voices was one that I hooked onto first and was like “How can you not love these guys?” I would slide him something. ‘Yeah! It’s great!”

We’re both Public Enemy fans from the beginning. We were insane about Public Enemy. That period of time between ’88 and ’92, rap music was the only important music being made. De La Soul. Public Enemy. There was so much good stuff coming out through that time period. We were both congruent on that.

I think he’s always definitely been into the darker stuff. I like it, But I think I’m a bigger fan of pop music than he is. So that would kind of lighten him up a little bit. It worked. We were a really good partnership, just in every way. We both really liked each other a lot and we were influenced by some of the same things.

Sarah: And you knew each other before college?

Jeff: No, I didn’t even – I was like the last person in the program to meet him. He kind of came to me last because I was never around. I was always doing stuff. But he was hearing all the results because he was listening to the station. I remember meeting him for the first time and he was like, ‘How did you think of all this? To go at CMJ and all that?” “I just talked to people. I just researched it and started calling people.” Back then, before cell phones, I racked up some pretty big phone bills at the school and they were a little alarmed by that. But I got a pass on it because of the results. All these records that were coming in that we were getting. And press that we were getting that drew some attention to the school. It’s funny how – well, it makes sense–there’s some attention that they liked and some attention that they didn’t like. They really liked the positive chatter that they would get in the newspaper because of what we were doing with the show and the things that people would say. But, play the ‘Thrill Kill Kult and Kooler than Jesus and there are all of a sudden one or two people that can throw the whole train off. “That’s blasphemy!” people would freak out.

Sarah: What happened with the Kooler Than Jesus video?

Jeff: I’ll tell you about that. We got kicked off of several stations in Georgia when we played Kooler Than Jesus. All it took was one time. They contacted Channel America and said “We want to get off of that show.” And luckily, like I said, we were friends with the program director. He was just like, “They really don’t like Kooler Than Jesus. This is down in the bible belt, so they’re really kind of freaking out about it. And they don’t want to run the show anymore.” “O that’s too bad. But whatever Because we’re going to do more of it.” We joked about it: “Hey, if you’re in Dublin, Georgia, see if you can pick up a signal in Athens.” We were still trying to communicate to them. It was a drag, too, because the stations that we lost in Georgia—we got mail from those places. The kids really dug it. But that was just a video too far for a lot of people. They complained. I’d think those folks would be in bed getting ready for church instead of being up so late on a Saturday night.

Sarah: They were busy getting offended.

Jeff: Yeah, that was funny. I interviewed Groovy Man a year after that or something and I don’t know if I told him about that or not. I’m pretty sure I did and I’m pretty sure he found it hilarious. He was a cool guy. One of the more interesting interviews to do. But that’s how that went. We were just on the air one week [snap] and off the next. All because of the Thrill Kill Kult.

Sarah: So when you were going through the videos, did you watch everything that you received?

Jeff: Yeah, we would. All that stuff came to my house.

Sarah: It was your personal residence?

Jeff: Yeah, and my basement would fill up. And I’d take all of the videos to Frank. They were usually on ¾”s. I think he had a ¾” machine at his place. And he would edit it all down to one VHS so that we could just run and watch the whole VHS tape and watch them all in succession. So, maybe 30-40 clips a week. And then we would take what we liked out of the new stuff, figure out how much time it would take. Can we fit it in? Do we play it now or push it off to next week? Is there something that we want to bring back from a couple weeks ago because we really like that track? We could shoot a clip out there, just play it one time, but you really gotta get it out there a few times if you really want it to sink in. There were some clips that were that good or that we liked that much. We would play a couple times. So it was kind of a mix of what’s new, and what do we want to really drill into people’s heads. Kind of make it work that way so that it’s fresh and strong. A fresh, strong playlist each week.

Your peak seasons are- I think releases probably still work the same- where, in the spring, you have a big flood of records come out. Toward the end of summer, when kids go back to school, there’s a big flood of records. And then around Christmastime, there’s usually a big last push of either new music or compilations coming out. So when it was a slower time of year, we would try to rework older things in, or go back to an artist that we really liked, something old, and try to pad the list out. Because we didn’t have new things. Depending upon what time of the year, we always tried to make it as new as possible, as fresh as possible. And then through repetition, work the things that we thought deserved to be pushed a little bit harder.

There was also, and this is one of the things that contributed to us not being interested in doing it after years and years of doing it was- labels were spending more and more money with us, and then, in turn you’d play the clips once or twice.

Sarah: What does spending more and more money with you mean?

Jeff: They would either buy straight-up a spot, or-

Sarah: O, you were playing for pay?

Jeff: We didn’t call it that, but that’s what it was. Basically. And we were increasingly uncomfortable as we did more and more of it.

Sarah: When did that start?

Jeff: It kind of always sort of went on but it became more and more blatant as time went on, I think. And that’s when we got less and less interested in it. The last straw for me was when No Doubt’s first record came out, the Tragic Kingdom. They bought the back page of the NoisePaper. I think they dropped like a grand. Which is ridiculous because we would print, maybe, 1,000 of those things, you know? It’s crazy. And then we would play the video. We didn’t push it that hard. One of the things was, we knew what they were doing. But what we would do is, we would stick Tragic Kingdom between Cows and Alien Sex Fiend or whatever. [laughter] And we wouldn’t even back-sell it. I think we back-sold No Doubt once.

In retrospect, it’s stupid because I actually like that band a lot now. At the time, it was kind of like, “What’s this ska/pop goofy music?” Not really recognizing that they were really a great pop band. I have a greater appreciation now for pop music than I did. I guess I did back then but I was fighting with myself all the time about it. But now I don’t care. If I like a song I don’t say, “It’s not punk enough” or whatever.

We were faced with that increasingly. Some labels were cool about it, too. Warner Brothers were very soft sell with, “We just want to but some advertising. Columbia, on the other hand, had a guy who was just a sledgehammer all the time: “Okay, so if I do this, what am I gonna get?” I used to hate that guy! I hated talking to him! I can’t remember his name. He ended up being like a VP somewhere, of course, because he was good! He was just a dick. He would never stop, you know? He was rewarded for all that. We just got increasingly uncomfortable with it. Yeah, it kinda was pay for play in a lot of cases.

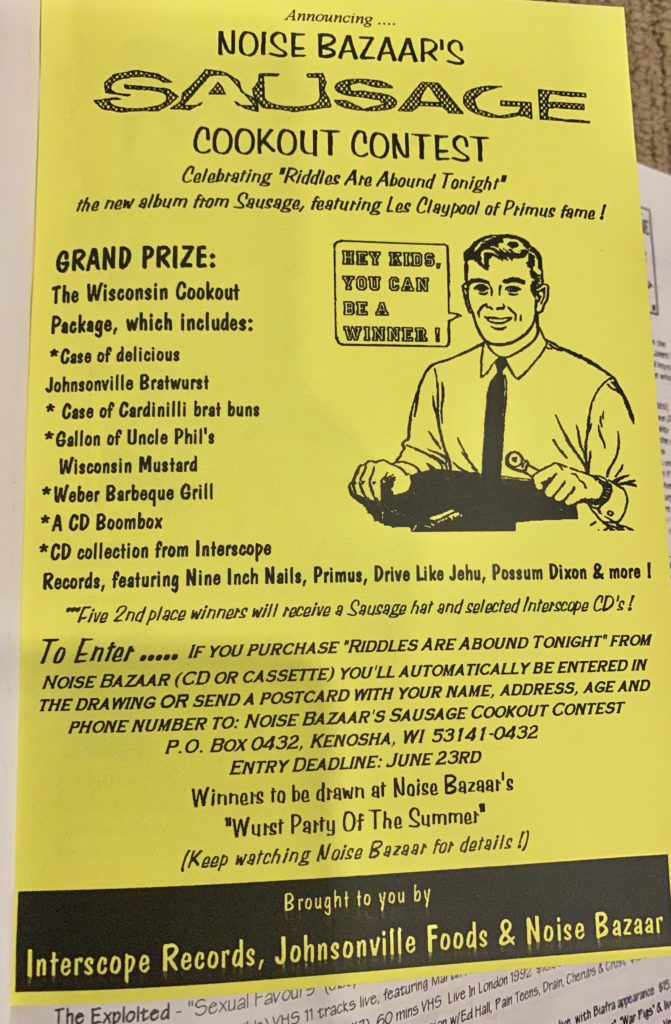

Or they would spend some money on advertising in conjunction with a special promotion. We did a sausage party before there was such a thing as sausage party. That was Les Claypool’s side band, [Sausage]. We just picked a bar in town. I think their promotion person at Interscope got a hold of Johnsonville Brats. Johnsonville Brats put up like 10 lbs of bratwurst or something like that for the party. And then someone could win a case of bratwurst. And then this cool Johnsonville/Weber grill cooler combination thing–we had some kind of crazy thing that we were able to give away for this party. They would put all these things together, and they would throw us some money for it. Consequently, some advertising would come out of that, too. There were a million different ways you could work that. Sometimes it translated into straight pay-for-play basically. We tried to avoid that.

“the wurst party of the summer”

Another one would be the Ministry Drive-By Vacation

Sarah: Yeah, tell me about that!

Jeff: I have a hard time remembering. I forgot a lot of that. I remember the sausage party one because it was a big all-day thing. But the Drive-By Vacation one was one that we did strictly on the show. We didn’t do anything off-site, and not a special show or anything. I just remember that one came through for the Jesus Built My Hotrod- it was kind of built around that.

Sarah: Who made those t-shirts?

Jeff: Uh, the label did. Warner Brothers.

Sarah: Really? It definitely looks like someone’s bedroom silkscreen project.

Jeff: I’m pretty sure that the label did that, and they paid for everything. As I remember they did a really good job of making it really—

Sarah: D.I.Y-looking. Yeah.

Jeff: Which was pretty cool.

Sarah: Do you think the label was like, “O we should make this a writing contest?”

Jeff: No, that was our idea. Yeah. We had a really good relationship with Warner Brothers. Wendy Griffiths, she was the person that we dealt with almost exclusively with video. And she was awesome. Always encouraging. Loved the show. Big fan of it. Most of the time they would just ask us. You want to do a contest? What do you want to do? Think about it and call me back. So we’d think about it.

The guy at Columbia always had a very definite idea: “Here’s what I want you to do.” But most people were different. They just let us come up with something. Or we would just collaborate together on something. I think Frank came up with that idea. Let’s do a drive-by vacation story. That was a good one. When you did a promotion, you either really wanted to do it. Or it was like, “O god, it’s No Doubt again. Okay.” But Ministry. Spend your money with us on that. That’s perfect.

proud second-place winner, about 30 years later and still beaming. photo by val moody

Sarah: There was Noise Network. Deciding to sell the music seems like a big step.

Jeff: Yeah.

Sarah: So what was that about?

Jeff: The Noise Network, the original idea was to be like an MTV if we could eventually grow it into a 24/7 channel. And I guess it was kind of the idea with Noise Bazaar, too. We’ll be on just an hour a week and do this whole constant thing where people want to buy records from us. They’ll get exposed to stuff and want to buy it from us and then buy it. So it was Noise Network before we came up with the idea of actually selling the records. And then we were like- what are we going to call it now? If we’re going to sell records, then what are we going to call it? And somehow we agreed on Bazaar. We liked the way it sounded. Is it bizarre? Of course it’s bizarre! No, it’s bazaar, like an outdoor bazaar. But that’s how that happened.

Sarah: How many years in was that?

Jeff: I want to say that it was within a year or two. I believe. The way I could really check it is to look at the old NoisePapers because really all the information from the show—I haven’t even watched an episode in, 20 years maybe. It’s been that long. At my birthday party, there was a clip from one of the shows. But that was the last time I’ve seen ANYTHING related to the show at all. That was six years ago. Before that, I hadn’t watched an episode in ages.

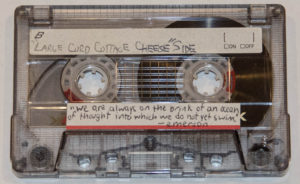

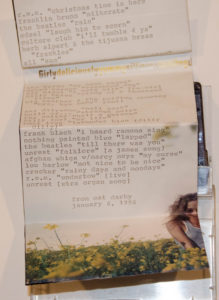

Sarah: One thing about the Noise Bazaar business model that I’m curious about is that when I looked back at the catalog that was in the Noise Paper, it seemed like you had just a handful of titles from a lot of different labels. So how did that work? Wouldn’t it have been more beneficial for the labels if you were like, “I’ll take fifteen of your titles or I’ll take all of your titles” or whatever. I mean, were they still happy to be selling you several copies of one title sometimes?

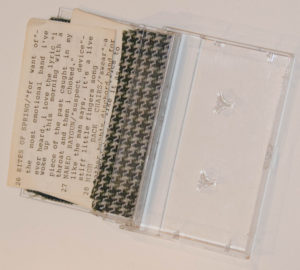

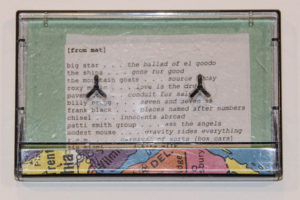

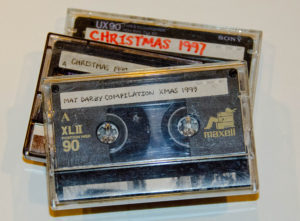

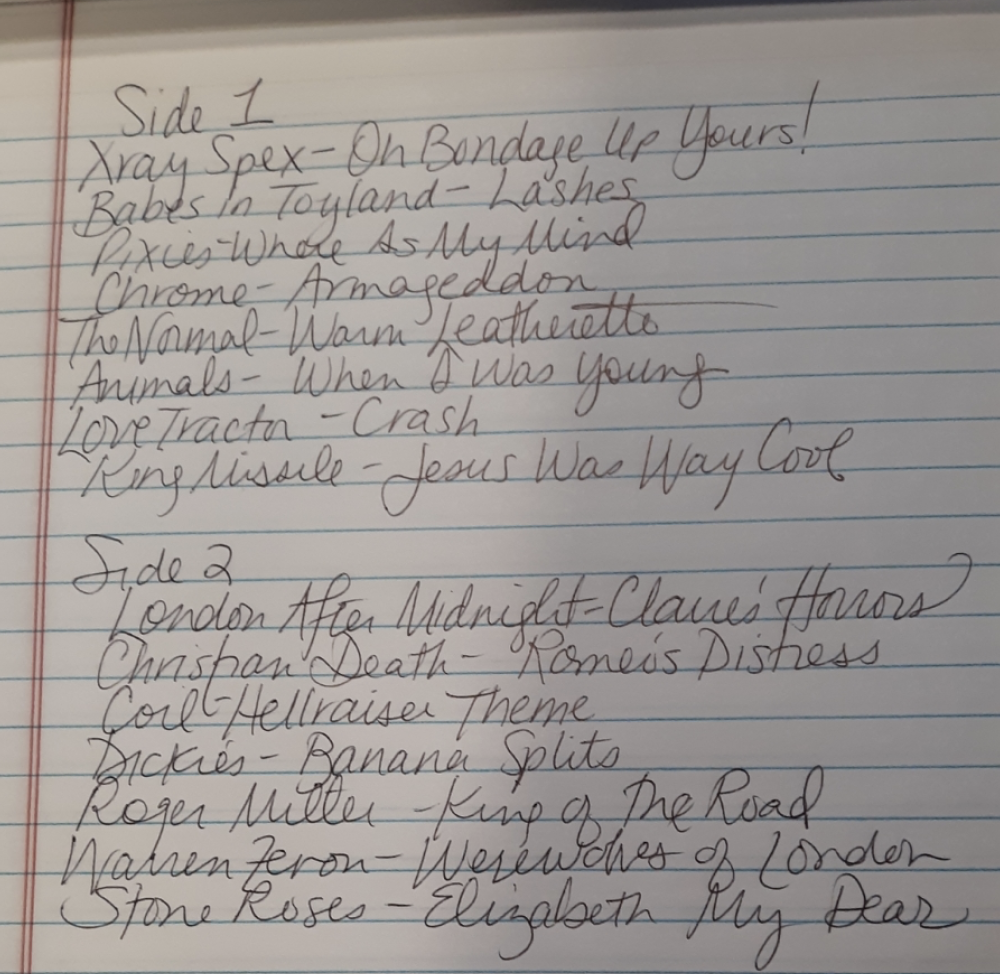

some cassette tapes purchased specifically because of a video on noise. notably missing here is galaxie 500, mazzy star, and snakefinger, among others

Jeff: Yeah. They knew that what we were doing was highly experimental. No one else was doing it. So, that got us a lot of—not clout—that’s the wrong word to use. But it’s the only one I can think of in this case. But it gave them a reason to say, “Let’s cooperate with this because if it takes off, there may be real potential here.” So everybody was really happy to accommodate us. What we tried to do is we tried to focus the catalog on the stuff that we were playing. Keeping it there. On most rosters, that was a small percentage of what they actually offered. Just to ballpark a number, 25 percent would actually get the budget to also make a music video. Because the label believes in them that much. And the rest, just put out a record and that’s it. We would focus our effort on whomever had the video we were playing.

If I remember correctly, maybe every biannually, we would put out a supplemental catalog that was more open to—it wasn’t on the show necessarily. But in the Noise Paper, we would offer more titles. More titles than we actually stocked but we knew we’d be able to turn around within a reasonable amount of time. 4-6 weeks, we’d try to turn these things around. We’d get an order from the person. Then we’d have to order from the label. And everything was done by pony express.

Sarah: Mm-hm. Who was doing that?

Jeff: Frank. Frank did the mail order.

Sarah: So you didn’t have extra help when you decided to become an entire retail operation?

Jeff: No, that was pretty much Frank. I’d get the orders. I’d give them to him. I did have some records stocked at my house, too, so I could fill some of them. But I mostly handled the videos coming in and dealing with the labels. And Frank pretty much handled the retail. I would handle the label promotion stuff and advertising. He would handle a lot of that, too. And organizing the interviews. I hated the interviews. I didn’t like to interview bands. I just didn’t enjoy it. There were very few that I enjoyed. But he liked doing it. And Frank was a really good interviewer. One of the best I’ve seen. You met J.J. last night, too. J.J. was a really good interviewer. Me, I’m too self-interested. I don’t care what these people think. [laughter] I just don’t. With the exception of David Yow. David Yow was the greatest interview ever. He’s the greatest guy.

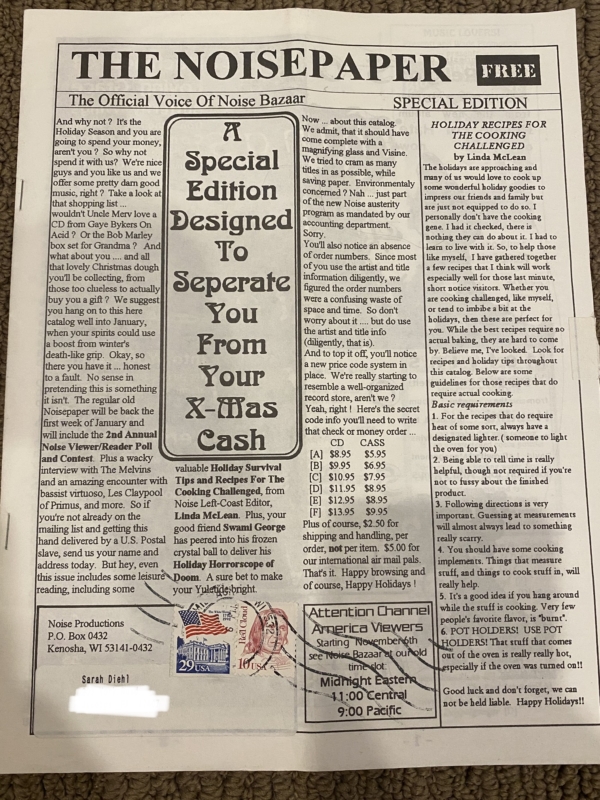

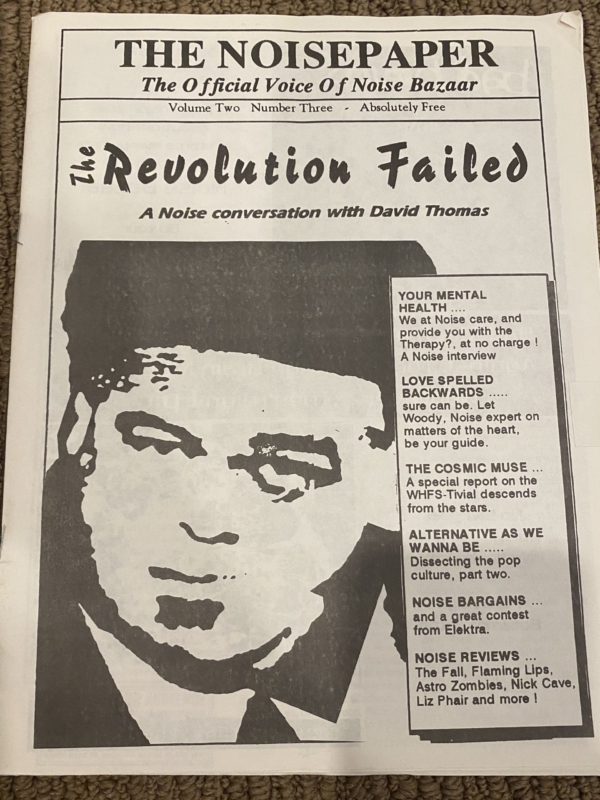

Sarah: Did the Noise Paper come right when Noise Bazaar happened?

Jeff: It did coincide with Noise Bazaar because we had this idea that it could be a fanzine and a catalog. Besides what people see on the television, we could bolster that with the purchase codes and stuff inside a magazine. Make a catalog. So yeah they did kind of coincide with each other. It was also nice, too, because we were kind of like, “Well, we’re going to sell records. Let’s write reviews. Let’s do interviews with the artists.” The interviews that we do on the show, a lot of times we could only show 5 percent of what we actually talked about. But when you write it all down, you can expand that format. You can’t put a 30 minute conversation on a video show because you’re not going to have enough time to show the videos. But you can put it all in writing, and people can go back and read it over and over. The two would work together in that way. That was the idea.

We wanted to write, too. I liked writing record reviews. It was just another exercise that was kind of fun. Frank was a really good writer. He was interested in doing that, too. We had friends that were like, “I’ll write a review! I’ll write a review!” J.J. wrote reviews for us. He did a great job. We had some writers who were good friends. I wrote under eight different aliases. Frank did, too. It was fun to make up names for all of that. It was definitely an offshoot of Noise Bazaar.

Noisepaper writer J.J., also at Thundersnow 2019!

Sarah: How successful was the mail order aspect of what you were doing?

Jeff: In terms of being a money-making venture, not successful at all. In terms of getting records to select kids who followed through and would order, and probably would have never gotten that record if they hadn’t gotten it from us- very successful. There were very happy people. So yeah.

Financially, no. But in terms of turning kids on to stuff and getting it into their hands, it worked for some people.

We made enough money to plough it back into the thing and keep making the show, keep making the fanzine. The show didn’t cost us that much to do because we had that relationship with Jones where they just kind of let us come in and do stuff. We used their studio for a few years and then we stopped using their studio, but we used to do it out of Frank’s apartment.

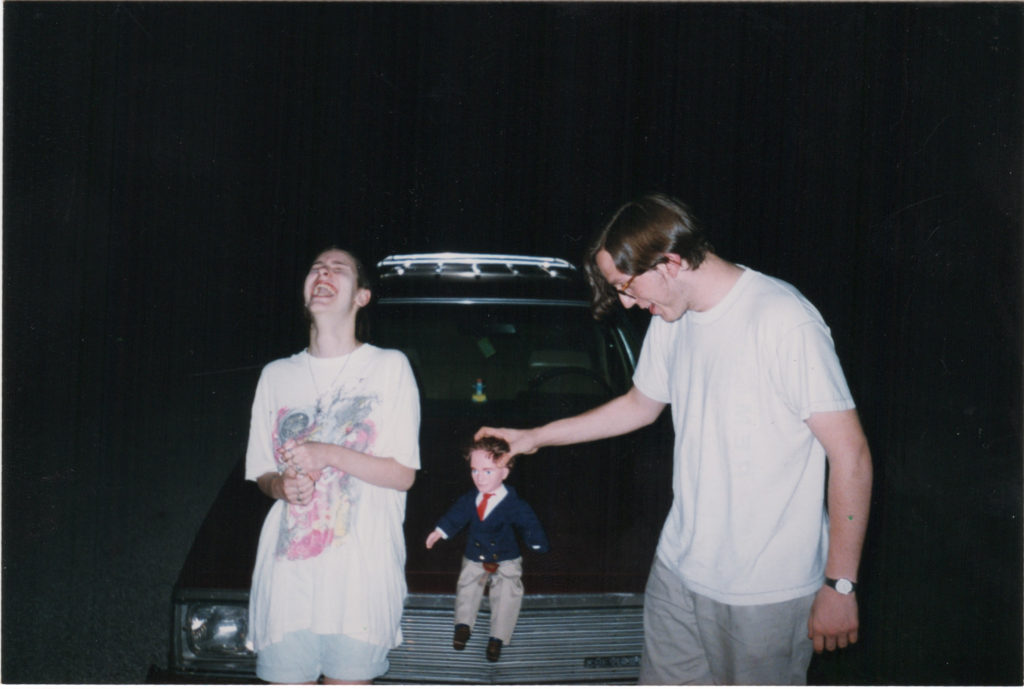

I don’t know if you remember, but we used to give things away every week, and we had the ghostly margarine prize bucket. Were you still watching during those days? We had the ghostly margarine prize bucket? I think it was later. The story behind that was that when they were in Frank’s apartment, Frank’s son was maybe seven or eight at the time, and there used to be around Halloween-time at McDonald’s this white pumpkin bucket that they would put a happy meal in. It was stuffed under the couch when Frank’s son was done playing with it. And one day, I was like, “We need to have something to put all the names in so I can draw a name.” So I reached under the couch and pulled out the thing. And we just called it the ghostly margarine prize bucket. It stuck and got really popular. We wanted to give it its own theme song.

There were a lot of things we did on that show. Do you remember Woody? The famous international playboy? It was just a mannequin head. And we did, like, clutch cargo lifts on him.

We started getting really fancy with cgi effects and clutch cargo lifts. 1960s technology in a 1990s video. Thirty years late.

Woody would read letters from viewers sometimes. Or he would give something away.

Sarah: Were you writing all the segues yourself and then reading them off cue cards?

Jeff: When we first started, I had this idea that it was going to really regimented and really scripted. But I wanted to write my own stuff. But after a while, it just got so easy and conversational that I would just ad lib everything. It was probably after like two years that I was like, “Ah, forget the cue cards, man.” Unless it was something really specific, like rules to a contest or something like that, then I would script it out. But it was much easier and much more fun to just ad lib it. So yeah, I would do it that way. It was fun.

That part was really fun. I was never uncomfortable for a minute.

Sarah: That’s a real skill.

Jeff: It’s not really a skill for me. It’s just like walking. I don’t know why, but I get on camera, and I don’t care. It’s just fine. It’s kind of turned out that way with bands, too. My stage banter is A plus. I can wing it with anyone, and I’ll be fine. It’s lucky that way. I get lucky.

Sarah: Tell me about when you felt it winding down. What were some of the early warning signs that this thing was gonna wind down?

Jeff: I had to work my regular job. I was taking on more and more responsibilities there. Same thing with Frank. And honestly he was doing way more work than I was. I was already overwhelmed by ’97. That was part of it. We were just burned out and tired.

A big part of it was that music was changing, too. When we started it, the whole alternative phenomenon happened. At the start of that, what the radio was calling alternative had a different meaning than college alternative, college rock, that was our thing. College rock was all-encompassing, everything from reggae to punk rock to black metal, whatever. The industry took that term and turned it into any band that sounds like Nirvana. Grunge. That’s alternative radio. Then, after ’97 or so, alternative started to mean Limp Bizkit, too. It started getting really kind of aggro. And I hate that stuff. I hated that stuff. And so did Frank. We saw that that’s where the money was being spent. Linkin Park. A lot of people liked Linkin Park, but it was passed me. I didn’t care for it. So, music was changing.

One thing we didn’t like as the whole thing was going on was that music labels were swallowing up the smaller bands from the indie labels; they were draining the indie rosters. When Capitol signed the Jesus Lizard, it was like, ‘What’s going to happen there?” At first, it was like, “Oh that’s cool, they’re going to make some money.” But you never make money with the labels because all they’re doing is they’re making an upfront investment, and then they’re going to expect a return on that investment. And maybe you’ll get your house paid for, if you’re lucky. But they’re going to own your songs. They’re going to own you.

What I didn’t understand about Capitol was, they grabbed the Jesus Lizard, recorded two or three albums, but never promoted them. They didn’t drop a penny on promotion. Touch and Go spent more money promoting them than Capitol did. Capitol has 80,000 times the resources. So, we didn’t like any of that stuff. My joke early on was, “I’ll believe this alternacrap thing is real when the Cows get signed to Columbia or something.”

We were tired. Things were changing. And we were getting increasingly uncomfortable with the pay per play situation, too, because it was getting more and more blatant. “We’re going to spend this much money. How many times are you going to play the video?” And it wasn’t just Columbia anymore asking the question. More and more people changed at different labels. That whole combination of things. We were just like, “That’s enough. Let’s stop. Let’s stop and take a break.” I was burned out.

But that was pretty much it. That was the end. I think it was pretty unceremonious, too. I think it was the end of 1997. We didn’t even do a “last show” thing. We just stopped. That was it. We gave Channel America a heads up so that they would know. The same guy was programming, and I think he told us, “We’ll just run reruns for a while, and if you guys change your mind, let me know.” But we were pretty solid on that. We were really done.

Sarah: And you both came to that at about the same time, you and Frank?

Jeff: Yeah! Into ’97, the beginning of the new year, we had said, “So, how much longer are we going to do this, really? How much longer can we go at this pace?” Because we were doing the show every week. We were doing the Noisepaper every quarter. For a while, we were doing a radio show, too. We were nuts. That lasted about two years. I think that was ’95, ’96.

Sarah: What was it called?

Jeff: Noise Bazaar Radio. That gave us a chance to [play music with] no video attached. Or, here’s an album and the cuts on the album. So it gave us a chance to do a little more. Or a band that we liked that didn’t have a video.

There was some guy with a satellite radio network thing that we found. Or he found us.

Yeah, after all that, by ’97, we were asking each other, “How long can we really keep doing this?” I knew Frank was really burning out. He was doing a lot. I was taking on more responsibilities at my real job. I became the trainer where I was at. Pharmaceutical industry training is nuts. It’s all paperwork-intensive. It was before all the electronic cataloging that you do now. Back then, it all had to be done by hand. It was a lot. It was super labor intensive. And I had more kids coming, too. I felt like I didn’t have enough time with the kids. A lot of different reasons. Frank’s son was getting into middle school/high school age, so requiring more attention. There was a lot. It was the right time. Seven years is enough, I think. That was the end.

Sarah: Do you have anything that you think about sometimes about Noise?

Jeff: Yeah, I often wonder. We were just ahead of the technology. I used to wonder, man, if the Internet would have come along just a little earlier, or if we would have been just a little bit later.

But it doesn’t really matter because Shawn Fanning in ‘99 did Napster. And that was the beginning of the end of physical product.

I used to wonder, “Should I have worked in the music industry instead of just working the regular jobs that I worked?” But I’m glad I didn’t because it would have been actual work, and I always wanted this to be fun. And not work. And now there’s no physical—there’s no record industry anyway. So who cares? And I never really cared much about that part of it anyway outside of- yes- getting this record into the hands of this kid in Kansas or someplace. That part was cool. But I never really thought of it as a real career option. But sometimes I do wonder.

I had a buddy. This was in ’99 I think. After we were done with Noise. He was a year ahead of me in high school. Or two years. He was an engineer. He was a brilliant guy, and he took a job at Bell Labs while he was going to college. And he’s still with Lucent Technologies. I saw him in ’99 on the 4th of July, and we were walking around. We were in this big field where there were going to be fireworks pretty soon. “Think about what you want to do with music in terms of delivering it to people,” he said. “because, I’m going to tell you, pretty soon everyone’s going to be able to walk around and access the Internet right where we are now.”

“What are you talking about?”

He said, “There’s no name for it yet. But it’s wireless technology, so you’re not going to have to be hooked up to anything to access the Internet like you do now.” Because it was dial-up at the time. He said, “you’ll just be able to walk around anywhere with it.” And there really wasn’t the smart phones that we have now.

I thought, “We’re not doing the show anymore. I don’t even know how I would do anything.” Spotify wasn’t even an idea.

That’s why I like Spotify so much, because if you had told me that I could carry the entire history of music in my pocket and access it, if you had told me that 25 years ago, I would have laughed at you. But you can actually do that now. I think it’s a miracle. I love my Spotify. Like last night- who’s this band? ESG! Boom, I’ve got it, and all night I’m going to be listening to that song cause it’s awesome. I love that kind of thing.

We had visions. All these things in order for something to be successful. All these things have to line up just right in order for it to work on any level at all. And it’s a miracle when it all does.

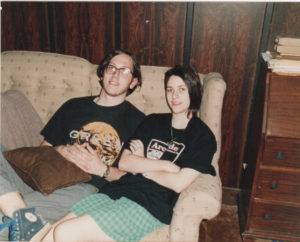

Jeff Moody was a co-producer and the host (known as HOST) of the nationally televised music video show and TV record shop Noise Bazaar from 1990 to 1997. In 2000, he began publishing Stripwax, the world’s only comic strip record review, which was published in dozens of alt-weekly newspapers around the US and Canada until 2013. Moody is the father of six children, works as a microbial environmental control specialist, sings in the rock band Fowlmouth, and occasionally hosts The PRF Radio Hour at www.radionope.com. He lives with his wife Valerie and their four dogs in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

jeff

Kelly: I think it’s weird now to think that—my whole thing with it was, “I’m in this little teeny tiny town, and I have my three or four friends here. And we all like the same music. But to find out that there’s other people somewhere else?” Now there’s the Internet and you can go on to Facebook and you can just google something. Then it was like, “Oh my gosh, I just got something in the mail that says that there’s somebody in another town, in another state that I’ve never been to before, on this little piece of paper, and they wrote all the same bands that I’m totally in to right now. And I can’t even believe this person exists because there’s only three of us here in this town. That would be so cool to write to them!”

Kelly: I think it’s weird now to think that—my whole thing with it was, “I’m in this little teeny tiny town, and I have my three or four friends here. And we all like the same music. But to find out that there’s other people somewhere else?” Now there’s the Internet and you can go on to Facebook and you can just google something. Then it was like, “Oh my gosh, I just got something in the mail that says that there’s somebody in another town, in another state that I’ve never been to before, on this little piece of paper, and they wrote all the same bands that I’m totally in to right now. And I can’t even believe this person exists because there’s only three of us here in this town. That would be so cool to write to them!”

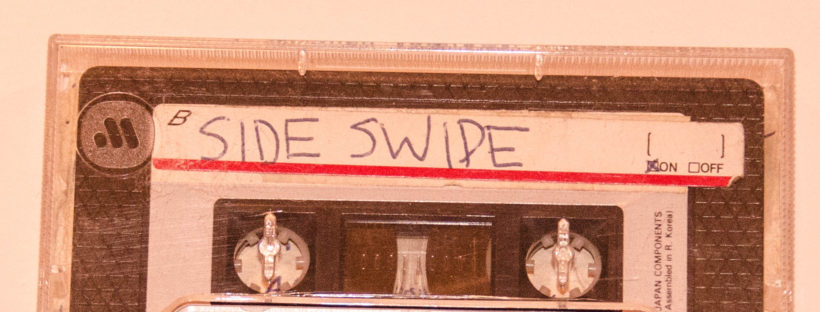

based on a little passage that excited you. Thinking about when we were in middle school or high school, something that you don’t experience too much anymore is the idea of hearing a song you love, having no idea who the artist is, and if it’s a new song, maybe you wait a week before you hear it again. And hopefully, the radio announcer says who it is. Or it’s on a friend’s tape and they tell you. But maybe a month – a year if it’s an older song – until you hear it again. And the rush of excitement you’d have –

based on a little passage that excited you. Thinking about when we were in middle school or high school, something that you don’t experience too much anymore is the idea of hearing a song you love, having no idea who the artist is, and if it’s a new song, maybe you wait a week before you hear it again. And hopefully, the radio announcer says who it is. Or it’s on a friend’s tape and they tell you. But maybe a month – a year if it’s an older song – until you hear it again. And the rush of excitement you’d have –

Jeff: Oh, man. My brother showed me how to do that. His Run DMC Raising Hell tape broke. He had a purple one. There were different colors. You could get like green, purple, yeah. And he had purple, as I recall. And it broke. This is like, again, third or fourth grade. And he had the whole – like my dad’s eye glasses kit with the little screwdriver. And he had the lamp behind him. He had this little station where he took it all apart and put it all back together. He took the tape from one of my parents’ bullshit tapes from their car or whatever. And replaced the little felt pad and did it all. Just tinkered his way into replacing it perfectly. It was impressive.

Jeff: Oh, man. My brother showed me how to do that. His Run DMC Raising Hell tape broke. He had a purple one. There were different colors. You could get like green, purple, yeah. And he had purple, as I recall. And it broke. This is like, again, third or fourth grade. And he had the whole – like my dad’s eye glasses kit with the little screwdriver. And he had the lamp behind him. He had this little station where he took it all apart and put it all back together. He took the tape from one of my parents’ bullshit tapes from their car or whatever. And replaced the little felt pad and did it all. Just tinkered his way into replacing it perfectly. It was impressive.