If ever this website was about seeking out people you like with whom you would like to be friends and from whom you would like to learn about music, this is it. If we were in high school, I would sheepishly ask this man for a mixtape. Since I’m an adult now, I asked for an interview. We can speculate on the merits of this pretense all we want. At the end of the day, I have come to believe that those of us who are deeply in love with music are wired similarly. And we should connect because of all the beautiful alchemy that may await. In the interview below I found that for music archivist, writer, and radio deejay Reuben Jackson, being wired to deeply love music has led to feelings of imposter syndrome, but also a triumphant embrace of the fact that “once something is in you, it is.” He embodies the mixtape concept, cross-pollinating music communities and influences, and eager to share.

Sarah: You were the kid who was playing music for all your friends. And you were saying that your parents played all kinds of music in your house. Could you say more about what it was like growing up in your house and how you developed this encyclopedic interest or knowledge of music?

Reuben: My parents belonged to—some people will get this, I guess—those record clubs they had back in the day. Like Columbia Records. You could get six albums for a dollar and with the fine print in the ad, you probably ended up hocking your house to pay for all these records. But this box would come every month, and I knew what that box was. I could read that it said Columbia Records. It might be Ray Charles, Beethoven, South Pacific. My father loved country music—Roy Acuff or something like that. Chubby Checker. It was this wonderful array of big band stuff that my father loved. I thought everybody was like this! And of course, my parents would play these records. We listened to this stuff as a family. In the basement, sometimes.

Also, I would spend time with them and see what this was. I mean, I knew who a lot of these people were. But, what’s this new album like? I just dug in. And then you start reading whatever constituted liner notes then. Who’s on bass? Who’s the banjo player on this record? “Recorded in Nashville, August 22nd, 1959.” So it all kind of started to sink in. A lot of that curiosity and desire for detail comes out of love. You love this thing. And you want to know more about it. And then the sound of it- like that line in Ray when Jamie Fox says, “We gonna make it do what it do.” And then you’re trying to figure out how it does what it does.

And because my mom played classical piano, I could ask her things about music. I could play her something and ask her, “What is this in the third measure?” And she was self-effacing about her playing. We had this little piano in the basement. She’d say, “Well, this is like a ninth chord.” Just to have your first fox hole. And someone who didn’t laugh at you for asking questions about music. As opposed to just sitting there bobbing your head—which is cool, too! But it was very nurturing where that’s concerned.

My brother had a little transistor radio, which I would sometimes borrow off his dresser, put the little earbuds in, and listen late at night and cover the light with the pillow. So I was always listening, certainly. That could have been mostly top 40 because of AM radio.

But it was like a house of music. It was safe. And I was naïve. I thought everyone liked music, period. We’d have show-and-tell in grade school. One day I brought Tommy Dorsey’s Orchestra’s Greatest Hits. And I’m thinking, “Everybody knows who Tommy Dorsey is.” He hadn’t been dead that long. It was sort of like one of these memorial albums. Here I am playing Sunny Side of the Street. The kids are looking at me like, “huuuuuuhhhh , this is not Motown.” And I was crestfallen. And it was my enthusiasm overriding any potential self-consciousness. Self-consciousness came when I discovered that people would laugh at you and say, “There he goes again.”

I think my work on radio and me working here [at the University of the District of Columbia] as a music archivist is kind of like revenge of the nerds, because as much as it would hurt to be labeled as odd or ostracized, I knew I wasn’t killing people. Once something is in you, it is.

Sarah: We had talked previously about how growing up you didn’t really think about genre-ization- you really didn’t know what that was. I was wondering if that may be a generational difference between the two of us. But your story leads me to believe that that’s not the case at all—that the kids you grew up with were interested in a few genres and were not like you at all.

Reuben: Yeah. Boy. About four years ago when I was still at Vermont Public Radio, I told my boss who was also at that time a programmer on VPR’s classical channel—I did a show once a month that looked at film composers from the ‘40s, ‘50s, and stuff. And I said to her, “I don’t like what is so-called classical music because it’s classical music. I just love – you hear something and it might be Schumann or it might be Debussy, but it had nothing to do with some hard and fast allegiance to a tradition.”

It’s the same with jazz. A lot of people say, “Well, he’s the jazz guy.” But those labels are funny because a lot of musicians who are considered this or this or this have interests far beyond what people might expect. Jimi Hendrix loved Schoenberg. He loved Andy Williams. He’d say this and the interviewer would be waiting for the punch line. And he’d go, “No. No. I’m serious.”

And I think for my friends. I love them. But if it wasn’t on the radio, It didn’t exist, basically. So that meant adherence, consciously or not, to a certain style of music. A certain sound. Whether they call it urban radio or whatever. R&B, I don’t know if that’s a style, like baroque music, or if that’s a cultural categorization.

The other thing growing up, too, is that after like ’67, ’68, and things were starting to explode in this country, there were- we called them checklists- how if you’re Black and you want things to get better, you have to do this, this, this, and this.

I once told a student that I was in the basement one day and my father came downstairs, and he took out a Count Basie record. Then he took out the Supremes and put the album on that side. And he took out a gun and pointed it to me- I’m joking!- and he said, “Pick one.” And then I said, ‘Well what if you love both?” And that’s the thing with me. You can love both. To love the Supremes doesn’t refute your love for Count Basie. Especially jazz people can be so, “How can you sell us down the river?” It doesn’t mean you love it less.

I think that also ties into what we were saying earlier about becoming yourself. If I had not been that way, beyond music, it would have taken me a lot longer to get here in general. And it has to do with music and life. So you meet somebody [now] and you can talk about all kinds of things. Like Russian Romantic poetry. It was in there [before] but it’s not the same.

Like being a musician and you play the same instrument. You’ll never know everything but you keep developing. And curiosity ties into it.

But I made fun of it. Like the comedian Bernie Mack said, “Humor comes from pain.” And I’ll hear silly stories about turning over the B side of some hit, and saying, “Listen to this countermelody. The French horn does this.” And my friends just start slapping their foreheads like “Damn, we were having such a good time. And there he goes!”

So it took me a long time to venture, not internally, but socially, in that direction, because I just thought, “Yeah, a lot of people just aren’t like this.” It can do a number on you. If something is such a big part of who you are or who you’re becoming. And you’re looking for people who are similar.

I saw one of these Quincy Jones documentaries and he said that he would cut school and go to the movie theatres. He was born in Chicago. His father moved the family to Bremerton, in Washington, just outside of Seattle, because his father was a carpenter and he worked in the navy shipyards. And he said, “I would cut school and just sit there. And the movies were okay. But it was the film music.” It was like Dmitri Tiomkin and all these people. And he said, “I just had to bathe in that music.” And I’m in the movie theatre. I’ve got a box of Kleenex on this side. I’ve got a box of Kleenex on this other side. And I’m thinking, “Yeah, that’s it. When it’s in you.” And how his father would surreptitiously slip him money for a composition notebook, because he knew it was in him. I thought they were going to carry me out of the theatre. “There’s some guy in here who won’t stop weeping.” The story itself is moving. For me, connecting with this thing that means so much.

Sarah: And so you feel you can do that now. And growing up, that might have been more challenging?

Reuben: It was! Growing up, you had to be a lot of things. I don’t want to overstate this, because I don’t want people to think I am trying to make it sound like I was in some Jay-Z video years ago. But what people call bullying now, I think that’s too nice a word.

I knew about three different ways to get home from the movie theatre because I knew who was on this corner waiting to take what was left of your money. Gangs then were like fistfight gangs. They weren’t like TEC-9s and Uzis. But that was a reality. So you’re negotiating a lot of things at once.

I think even now, though, for men to be received as soft can be a challenge. I can’t say this was a cover because I was good at sports. I was a little more respected. I could play ball. Football, baseball, and all that. But I think it is a lot to handle at one time.

There were also guys in my neighborhood- by today’s standards, they would be considered quaint. Some of them dropped out of school. You’d see them. They knew when the report cards came out like they were school administrators or something. They would see me walking home from school. They called me “Bookworm” because I was always with books. “Bookworm, let me see your report card.” They’re saying this before my parents. This one guy, Clarence, would say, “Yeah, you gotta tighten up this math grade.” And I’m thinking, “They’re looking out for you.” So you have people looking out for you. And then people who can’t stand you because maybe your teacher is going on about some essay you wrote. And they want to beat your ass at 3:00. That’s too many jobs for a kid. Being a kid is hard enough.

I taught high school English for two years. I thought it made me a better teacher—not that you want to go through all that to become one. But It’s an understanding that at best the subject matter is secondary, maybe tertiary. It’s part of your development. I remember the kids would bring things into the classroom, whether it’s discussed or not. Because I did.

Brightwood Heritage Trail marker, photo by Devry Becker Jones

I loved my father. My father was also a functioning alcoholic. I grew up in Brightwood [in Washington D.C.]. The house was small. I would try to hide his bottles before he got home. Well, in a small house, you don’t have that many places to hide. But I knew he couldn’t bring it up at the dinner table to my mom. He was supportive, and he had a problem. I think ultimately what happens is—and this is true of both myself and my brother—in a parent you hope for “better” for your children. What if “better” is different- like so different that you don’t quite get it?

So in my case, the geeky music loving kid – [as an adult, working] at the Smithsonian, and I get to go to conferences all around the world and all this stuff. I have this indelible image of him: One of my first books of poetry won the Columbia Book Award, and they had a ceremony at the Folger Theatre. And Joseph Brodsky chose the book. And I’m sitting on the stage, and they’re reading comments from Joseph Brodsky. My mom was a Language Arts teacher for DC Public [Schools]. She was the extrovert of the two. She’s beaming like those lights on the top of the Empire State Building. And my father, dressed to the 99s, he’s proud, but he’s a little like, “Who the hell is this dude?” Even though we had a common love for music—like, I love ballet and opera—he’d say really nasty things about that. It’s like the combo platter.

Sarah: Man! Okay. I went with you on that journey and I’m not thinking about music any more. I think when we first started talking, you were talking about getting your friends to listen to some particular technical aspect of some song you were playing, and to me that was kind of a corollary to the mixtape idea, where you’re sharing music with people. So I’m a little thrown that we are actually talking about how hard it was for you to do that! But, that must have changed as your life progressed.

Reuben: Well, you find vineyards. I started doing radio when I was 18 at Goddard College in Vermont. And that was an outlet for both the continuation of sharing music and in a personal matter, it’s a way of dealing with all your feelings. Programming is like baking the cookies, but you’re baking them for other people. They really aren’t for you. And I think learning that is important.

But I always felt different. My first year of college, my show was Tuesday night, 9 until midnight. I’d go to bed early Monday night. I’d eat dinner, go back to the room, I had this whole ritual before I’d go to the station. And it was kind of funny but it was serious because it was this thing you love and you don’t want to mess it up.

You know- college radio, a lot of our friends had shows. And their friends would come to the station during the show to hang out and talk. And people would say, “Hey, can I come by the station?“ I would say, “No. ‘Fraid not.” Because it’s my time. I cut out the lights above the board. I got the playlist. Any notes I needed. That was me. So, that helped a heck of a lot. And like with poetry, I didn’t know I was going to fall in love with it to the extent I did.

And then the other surprise was that fall 1975, someone calls the dorm, the dorm phone in the lobby. Someone said, “There’s some guy on the phone for you!” So I come downstairs. And it’s the program manager for WSKI. It’s a country and western station in Barre, Vermont, which is the granite capital of the world. So this guy said, “I heard your show when I was driving.” At this time, the station was 10 watts. So he must have stopped and hung out by the gas pumps at the general store. Anyway, he said, “I think you’re like the best announcer in the state. Would you like a part-time job?” When you’re an undergrad, you don’t have that much money. And I said, “Okay.” He said, “Well come by the station Friday, and we’ll talk about it.” So I get this program. It’s 12 to 3 on Saturday. Country and western. Merle Haggard, people like that. A proscribed playlist. The station is about the size of this table. At the top of the hour, I read the mutual teletype. Rip and return. “Today, President Nixon…”

There are more people of color in Vermont now, but it’s the second whitest state in the country. But at that time, If I saw someone Black I’d call all my relatives, “I saw somebody Black!” So imagine you’re 18, you’ve got this job. This station. It’s a small place. They know your voice.

Image of Barre, VT from Royalbroil on Wikipedia

So you’re at the grocery store, at the deli counter, and you’re getting an egg salad. People start turning around like this. “You’re that guy!” And they don’t mean anything by it. One day I was there, and this woman was with her husband. And this woman turns to her husband and says, “It’s that colored guy on the radio!” That’s what they know. It’s so isolated. I said, “Yes ma’am.” And she said, “You’ve made Saturday afternoons. We just love your voice, and of course the music you’re playing.”

Well, I’m from here [in Washington, DC]! And I grew up ducking gang fights and stuff, daydreaming. And it’s not like “Look at me!” But here you are, in this place where people just stare at you sometimes. And suddenly, by way of music, you’re part of a community in a way that you wouldn’t necessarily be as “merely” a college student.

And of course, the difference between these two things is, even though I had a certain format I did with the college stuff, this was all you-play-the-hits. Part of you is like, “Am I selling out to the man?” And the other part- the ham part- is, “This is fun.” It can be fun to walk down the street and the pick-up truck goes by and people wave, and I’m thinking, “My friends would not believe this.” I think it comes from opportunity and people thinking to give you a shot. And it’s an extension of having heard so much stuff—getting back to my parents’ house and all- and never surrendering my love for music.

Sarah: So, let me ask you: as you got to know who your audience was—who you were baking the cookies for—did that change what you were baking?

Reuben: I don’t think so. I would call myself, and I have been called, a cross-pollinator, One of the nicest, most moving, and perceptive things anyone ever said about my radio show for Vermont Public Radio was, this woman said, “My family and I really appreciate what you do. No matter what the piece happens to be, you’re trying to point out where the jazz is.” And I started to cry in this grocery store. Because that’s really it. But first and foremost, it has always been: Isn’t it wonderful that this exists? It’s a little quixotic. But I feel that way. And I still marvel at the wonder of creation. And I think that’s never changed.

On Sundays, I do this show with Larry Applebaum on WPFW called The Sound of Surprise. It’s 4-6. You get phone calls from people who are appreciative because they’ll hear things that’s maybe a little different from typical jazz radio. I think jazz radio and classical radio can be similar—and I understand that there’s revenue involved- but, the strict adherence to the canon.

For me, like the joke about Count Basie and the Supremes, the continuum doesn’t mean that the other stuff is not of value. It’s like, isn’t it great that these elements are found in some seemingly disconnected source?

I’ll play Lester Young. For me, he’s one of the most original people, no matter what. And I think, “Boy! It’s like Ezra Pound, the poet. Make it new!” It’s fresh. To go from that to a new recording. This kind of bothers jazz people.

There’s some new version of a tune from the late ‘60s- which was a while ago now- but that adherence to stick to the standards, the 32-bar songs, the Gershwins and what-have-you. You can love that, too. I try to give as much of a sample-of a smorgasbord- as possible. And you do it the best you can in terms of coherence. But it’s for them. Maybe the audience are like the kids in the basement I don’t see. (Except they will call.) But I’m convinced it’s an extension of that: Isn’t this great?

This guy, Ben Williams, is a bassist from DC. He did an album. He had a subtle bass rendition of that song Nirvana did- Smells Like Teen Spirit. That’s a standard. This guy’s studying with Christian McBride. And he can talk about Mingus and all these people that are sanctioned. And you hear from people that are saying, “I never knew jazz people COULD do that.” Like maybe they broke out of jail. [laughter] It’s interesting to work within those rules and unwritten rules about this.

My bosses were kind of ambivalent about jazz to begin with. And maybe I used that to my advantage. I think of that character the Hulk, David Banner, and then the big green bicep starts to pop out. But it’s still all done for the listener. And it all comes from love. It’s not like thumbing your nose at people. It’s fun, but when the woman said that about pointing out where the jazz is, I thought, “Okay. She got it.”

Sarah: She got it. I would like to ask you what you are trying to showcase and why. In all the venues that you’re sharing music, like radio programs or what-have-you, what are you trying to showcase?

Reuben: I’m thinking of an interview that Charlie Parker did in the early ‘50s, when he said that there was no boundary line to art. And the thing about music- it’s so vast. I think of the vastness of music. If you just say “music,” you could be talking about Buddy Holly, you could be talking about Fugazi, you could be talking about the Spinners, or Mendelson. It’s like- freshwater, salt water. And so I think the immensity of it.

I think one of the good problems to have is that most people will never hear even a smidgeon of it- even, we were just talking about what is called jazz. You’ll never hear all the stuff. And to try to share some of it- it can be overwhelming. It’s a good problem to have, the overwhelming variety and beauty in spite of societal conditions which in many ways, especially with Black musicians, made their lives hell. People can- you could blow up buildings. You could knock somebody on the head on the street. Or you could do this. AND you could do this. So, if you think about what humanity is capable of, there is that, too.

I’ve been preparing a talk about the lesser known works of Quincy Jones for the last couple of weeks. So there’s like film score stuff. Some big band charts he did for people like Lionel Hampton and people like that when he was like 19 years old. TV stuff. People may remember it or not. It’s like that kid in the basement saying, “Yeah, but there’s also this!” There’s the score from the movie In Cold Blood. So it’s variety, immensity, possibility. What’s that thing Patti Smith said? The sea of possibilities. That’s really it, it’s the sea of possibilities.

Sarah: That is beautiful. So, we also talked about how you and musicians you admire are always looking for something different. So, how was that done in an era before the Internet (where it is so easy to find new and different things)?

Reuben: How was it done?

Sarah: How do you find out about something that you don’t know about?

Reuben: I see. Yeah. Every now and then I hear myself saying to students, “Well, you know, there was no internet back then!” And I feel like Samuel Morse’s homeboy or something. It took a lot of digging and curiosity. Because even then, even with radio and artists, like you could live here and hear about some great jazz station in New Orleans, but you couldn’t necessarily get it. You could read Downbeat magazine or something like that. And there were record stores. But I’d say even up until relatively recent times, the record stores here weren’t always that great.

My restlessness and curiosity—if I’d hear about some book somebody’s written about ‘50s jazz in Sweden, I would go to the Library of Congress and just stay all day and read stuff and take notes. When it was cheap—and this was even in the 90s—when it was cheap to take the train to New York, I’d go to New York and hit these jazz record stores that someone referred me to.

So- word of mouth, the few periodicals which existed at the time. Downbeat. There’s one called the Record Changer. But, it was hard!

Or maybe your hip neighbor who might know something. The cool outcast. I used to always say, “You have to dig. You have to dig for it.” And it’s kind of lonely. But I was on the road. I couldn’t stop. While these weren’t always things outside the “mainstream,” my parents’ tastes helped. Because if you’d hear some drummer on a record, I’d want to know more about them. It’s funny in thinking about this, see I’m saying this to you now, but partially when 2021 hit, I’m thinking, “I’m going to take out my phone and type it in Notes.” But see, you weren’t doing that in 1969. Or much longer than that. But that’s where it helps for me.

Again, like in New York, some store, a guy says, “Yeah, I have this record” and pulls it off the shelf. You might pay goodness-knows-what. It was a more circuitous path. I’ll put it like that.

Sarah: So it sounds like you may have had an outsider neighbor here and there but it was really your parents more than anyone, when you think of the key figures.

Reuben: Yeah. Some of the stuff left them scratching their heads. Things that they just didn’t get. That’s okay. That happens with everybody.

In 2009, I gave a talk at the Museum of Bethel Woods. Bethel Woods is where Woodstock took place. The emphasis was on the last year of Jimi Hendrix- ’69-70- what changed compositionally. So you’re in this auditorium in the museum. First thing, walking around the grounds, I was like, “Damn, this is like my Gettysburg.” Not a war. But stuff that’s really in your head and heart. So I got up there after being introduced and I asked everybody in the crowd, “With left or right foot, [give me] four quarter notes.” [stomp stomp stomp stomp.] And people are thinking “What the hell is this?” Anytime I played Hendrix in the basement, my mother would say, “It’s too loud!” And she’d go [stomp stomp] three four shut up.” I said, “So we just brought my mom back.” That’s an example of, “We don’t get this.” That talk [at Bethel Woods]- it’s that nerd stuff. And isn’t it great?

I once caused some stuff at a class at Goddard. It was called the History of Western Music, and we were talking about compositional devices. And there’s this concept called contrary motion. And the teacher played a piece from Stravinsky. And I went, “There’s a record by Kool and the Gang with the same thing! Can I bring it in next week?” What’s the name of that song? Who’s Gonna Take the Weight. I offended some people. “You aren’t possibly comparing Kool and the Gang to Igor Stravinsky?” I said, “We’re talking about the use of this technique. Boom. Kool and the Gang, Jersey City, NJ. Stravinsky, Russia. Boom. That’s what it is. And if you like it or don’t like it, there’s nothing I can say about that. But I think it worked.

I love Stravinsky and Kool and the Gang. And for what it’s worth, someone asked Stravinsky, after he moved to America, “Who do you like? Who are your favorite composers?” And he said, “I like the three B’s.” The interviewer said, “The three B’s?” “Yes, Beethoven, Bach, and Brown. James Brown. It’s the American sensibility, and he’s a great composer.” This still baffles people. Stravinsky- you talk about “mad skills” as the kids used to say. I always said he had the funk in him. That rhythmic stuff if you think about the Rite of Spring. And then you put on James Brown’s Funky Stuff and you think, “Yeah of course! They’re coming from the power of rhythm.”

Fortunately, there are some people out there, like airwaves, that think this way. It does knock down a lot of things in people’s heads, understanding that it’s not a crime to love all of this. Again, it’s that immensity.

Do you know who Michael Tilson Thomas is? He’s a conductor. He’s been with many orchestras. There was an American Masters last year addressing his life. He was talking about James Brown. I met Michael Tilson Thomas in 1971. James Brown was here. He played the Howard Theatre for a week. There had just been an article in the Rolling Stone magazine about Michael Tilson Thomas. He was the young person shaking up the classical music repertoire. He was with the Buffalo Symphony at that time. So intermission. You’re in the john. There’s like one white dude in there. And I knew that’s who it was because I had just read the article. So I waited. I said, ‘Aren’t you Michael Tilson Thomas?” He said “Yeah.” I said, “I read that article about you in Rolling Stone.”

So he’s talking about this in American Masters, and he says, “Well, when I conduct Stravinsky, I try to get that same kind of precision that James Brown had.” James Brown referred to it as the Situation of Music. I don’t care if it’s Emmylou Harris or Chuck Berry. It’s the situation of music. If we’re rehearsing and someone says, “What do you want from us in this measure?” He says, “I want you to break out in a cold sweat.” So he’s doing James Brown. And that’s somebody who’s not saying, “Well I can’t say this because it’s not classical.” And he wasn’t trying to be cool. I think for him, too, it’s like, “Isn’t it wonderful that this music exists?” “While I was in conservatory, we were all studying Stravinsky, but we were listening to James Brown.” It’s generational perhaps. But still, what’s being done within someone else’s work and how does it work? That’s no different than Jo Stafford or anybody else—what happening with the orchestration? Like anything, what is it communicating? Is it communicating something?

To me, the Jo Stafford thing. She’s like [swooning sound.] She’s like up there with the ability. You can play soul and science. She’s got perfect pitch. And a very sagacious vocalist. You believe her. My mother used to play this recording of Some Enchanted Evening. And I’m thinking, it’s like she’s my sister and she’s telling me. And I’m thinking “What is going on with life?” and she’s telling me “Some enchanted evening you may meet a stranger.” And I’m hanging on the words and the beauty of it and the sincerity. And the sincerity in music, if it’s not there, it’s just technique. It’s got to have that feeling.

Right before I took early retirement from the Smithsonian, December 2009, one of the things I was hell-bent on doing was to get her to donate some materials to the Museum of American History. Right after the World War II memorial was dedicated, American History had this weekend of all kinds of programming connected with that. I gave a talk about her. A lot of times they would play her music in barracks before G.I.s went to sleep. They called her G.I. Jo. There’s this beautiful essay by a guy names Gene Leeds called The Voice of Home. She was called the Voice of Home. So you’re looking out in the auditorium and it’s like all these WWII guys and families. I mean this lovingly—old dudes. And they’re crying. And I’m thinking, “I knew. But I didn’t know.”

I reached out to her. I wrote her a letter. One of my former colleagues had her address. And I get this letter back. It’s that old cursive writing you don’t see anymore. Jo Stafford. And her husband had just died. I wrote to her, “I’m approaching you…your story is an important part of the American story blah blah blah” I said “I’m going to be in California in the L.A. area in the next three weeks. Is it possible to talk with you more about this?” And I’m thinking, be ready for the big “no.” She wrote, “That would be wonderful. Let’s get in contact right before you leave and we can have lunch.” Okay. My heart is Jo Stafford. This is my job. And it’s like my parent’s basement. So I go. She had a condo in Century City. We spent a couple hours talking and carrying on. She made lunch. She’s so unpretentious and funny. And I told her about my parents.

She is someone who quit the business at the height of her popularity because of her kids. She said if both parents are working, this is not good. This was late ‘50s. At that time, she was making big money. So I’m leaving her condo and I’m on cloud 99.

Then two weeks later I get a letter. She said “I hate the telephone,” which made me adore her even more. She said, “I was talking to my son about it, and I don’t think I’ve really done anything to merit this. But I really appreciate your request.” The irony to me was at this point those big congressional allocations we would get for years were starting to dry up. And I think a lot of yahoos with some half- interesting stuff and a lot of money to pay for cataloging and processing were suddenly more attractive to the museum because Smithsonian needed the money. And I’m thinking, “Here’s somebody who sustained people during a time of great tragedy, sacrifice, and she’s too modest to do it.” But I still have those letters.

She has a version of the folk song Shenandoah. Now with COVID and thinking of travel and loss and not seeing something or someone, it always has this added resonance for me. But it’s always been there.

Anyway, same for Karen Carpenter. Oh my god. You talk about somebody that’s believable. Plus she was a great drummer and didn’t get props for her musicality. “It’s going to take some time this time.” And you hear it and you think, “Yeah, this happened” And it doesn’t matter if it did or not. You believe it. This vocal is so fresh and sincere. And those kinda gooey suburban white picket fence harmonies underneath it. And then this guy Hal Blaine, a great session musician, he’s playing these beautiful things with cymbals. See, this is what my friends put up with. It’s all going on concurrently. And you think it’s like you got Newt Gingrich and Bernie Sanders together in the same room. But it’s all part of this thing. And it all goes back to isn’t this wonderful? It can be the entire piece. It can be like 4-5 measures.

I used to sit on the stoop of my parents’ house just kind of hanging out. And I think about my mom, who would embarrass me [about my career and travel] if she were alive: “My baby’s at a repository in Germany.” And I get kind of weepy about it. But I’m thinking, “Well the stubbornness kind of paid off.” Not that my aim was to be documented somewhere. But I’m thankful that that’s the case.

And I talk a little bit more now about stuff that I’ve done that I didn’t do before. I was a voting member for the Grammys. It’s been a wild ride. You find yourself in these ballrooms with all these people and you kind of act like, “O yeah, I do this every day.” And there’s Dionne Warwick and Ringo Starr or whomever. But when people see who you are, name tag and all, you can’t act like you don’t belong. I have to kill the second grader being worried about getting beaten up for being a nebbish.

My mother used to call DC a big, small southern town. Which I think it still is, even with these incredible changes which have occurred. Like a lot of small towns, there are people who look askance at people who– “You got this job. You do all this travelling. Don’t think you’re better than we are.” I don’t.

I would go to Sweden or somewhere for a conference. I’d come back. I’d go to the barber shop. People would say, “Where you been?” I would never say anything specific. This is my problem. But I didn’t want to risk having to deal with people who are like, “Who do you think you are?” So I stuffed a lot of stuff in the closet.

The Smithsonian had this big gala on the Queen Mary to get moneyed people to donate money. I’m staying at this hotel. It was black tie, which is funny enough just to see me dressed up. They had all these limousines leaving the hotel and heading to the ship. I missed my limo. And someone: “There’s one down at the end there. You can get into that one.” So I get in. You should live as long as this limousine! I get in the back and see this woman to my immediate left and I say, “Good evening.” Sitting across from me is Elizabeth Taylor.

You’re from 5th St NW, and you’re looking across at Elizabeth Taylor. So we’re chatting on the way to the Queen Mary. And it’s that, “Okay be yourself.” But the other side of your brain is going, “It’s Elizabeth Taylor!!!” I still don‘t believe some of it. I don’t know about “job of a lifetime,” but 20 years is a long time in the course of one human’s existence. I’m still unpacking a lot of this stuff. My mother would say if she were alive, “My god, you were even dressed up!”

I think I’ve succeeded despite myself. “Is it okay to do this? Is it okay to be this person?” I did dream about some things. I’d read liner notes and wonder how do you do this? How do you get to do this? When I was a kid, you didn’t really see many Black writers. I saw that Langston Hughes had done some. I thought “Maybe. Maybe.” But I kept it filed away. And when I had the opportunity to do it, to be considered for a membership in NARAS, you have to have a minimum of 12 liner notes credits. I had 15. They were looking to broaden their color spectrum with voting members. I said to my mother, “I have 15.” She said, “Just stop right there. Even if you don’t get in, just look at what you’ve done.”

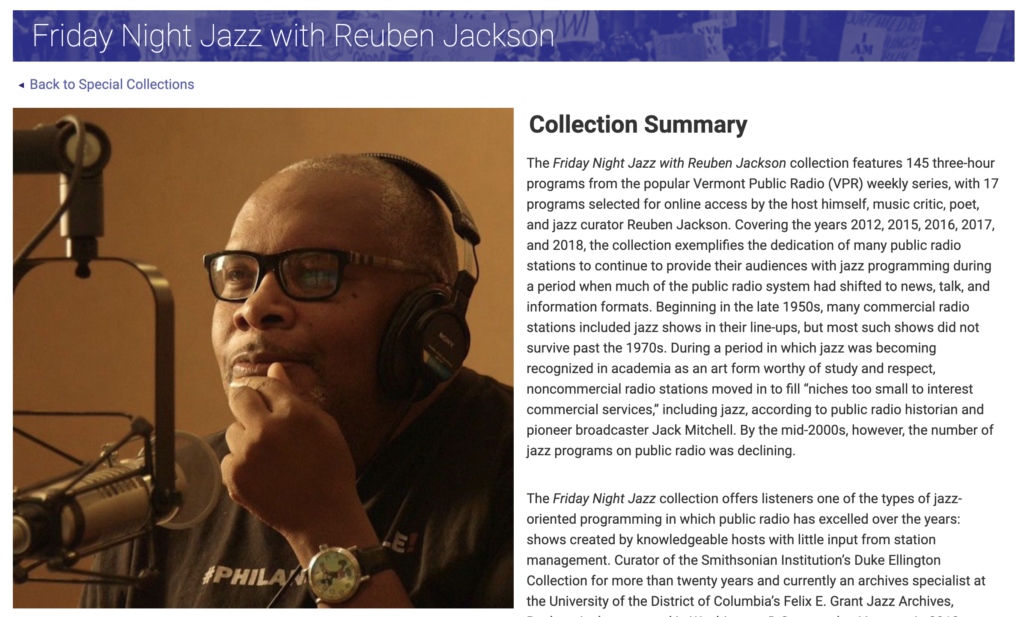

Reuben Jackson is a Washington D.C. poet, jazz archivist, radio deejay, music lecturer and writer, and writing mentor, but in what order I cannot say. He currently works as an archivist with the University of the District of Columbia’s Felix E. Grant Jazz Archives. His two poetry collections are called fingering the keys and Scattered Clouds, respectively. One of the first things he told me is that he doesn’t know bupkus about mixtapes.

Reuben