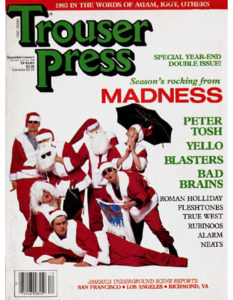

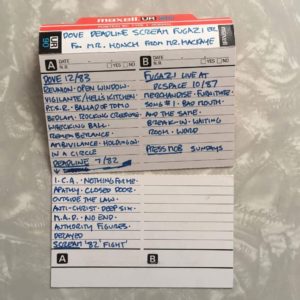

One afternoon in October, I left Dischord House in Arlington, VA feeling inspired. The premise for meeting up with Ian MacKaye was that Michael Honch, former member of Hunger Artist among other bands, had a tape that Ian had made for him before they had ever met. This fact alone astounded me. In 1987, Michael wrote Ian a letter to ask for a recording of the Washington, DC band Dove. In response, Ian made Michael a tape with Dove, Deadline, Scream, Fugazi, and Press Mob and sent it back to him in Rochester, NY.

The letter and tape exchange had happened long before any of us knew one another, when Ian was seven years in to co-running a landmark independent record label and just beginning to play shows with Fugazi, when Michael was struggling with his first year of college, and when I was struggling with my first year of middle school. Nevertheless, when Ian and Michael and I met up to talk about the tape, we whiled away the time like old friends. The same culture of camaraderie and music sharing that encouraged the 1987 exchange inspirited the afternoon. Our conversation meandered through punk and Dischord anecdotes to the meaningfulness of true connection with others. It was the kind of conversation that leaves you changed, renewed, affirmed. It is an honor to share it.

The conversation begins after Ian blows our minds by throwing the letter that Michael had written him onto the table in front of us.

Page 1 of Michael’s letter to Ian

Michael: This is incredible. I was telling Sarah, the first time I’d ever heard of the Internet, a guy I knew in Rochester who was a little older, he worked for Xerox, said, “I met someone on the network, and he has the Embrace demo.” And I was like, “Okay forget about the ‘network.’ What?” And he was someone who was communicating with this early tech communication.

Michael and Ian

Ian: You actually say in there- you say my lyric writing’s gotten better [laughter], which I appreciated. But you also say that you’re looking forward to hearing this new project of mine, which was Fugazi. You’re very well-versed in DC punk.

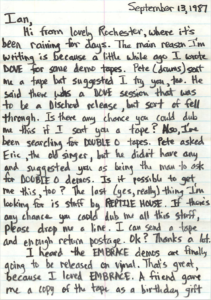

Trouser Press magazine cover with Bad Brains

From trouserpress.com/magazine

Sarah: Yeah, so how would you have known about that stuff happening?

Michael: Growing up in Rochester in the pre-Internet days, it was hard to get information. I’d hear about things. I think one of my introductions to punk rock – I liked David Bowie. I liked Iggy Pop. I liked the Ramones, things like that. But I wanted to know what was going on right now. This all seemed like way in the past. I remember going to a bookstore and reading in Trouser Press magazine about the Bad Brains. And I was like, “Oh! This sounds like what I’m looking for.” I couldn’t find this anywhere. But I bought the magazine. My dad was taking a business trip to Boston, and I said, “If you see the Bad Brains tape in Boston, will you buy it for me?” And he found it.

Ian: He must have gone to Newbury Comics.

Michael: Yeah. So he bought the Bad Brains ROIR tape, brought it back, and me and my friends all gathered around that tape. That’s where it all started for all of us. So when you’re trying to learn and figure out your own deal based on recordings, you’re still behind what’s going on right now.

Ian: What does that mean?

Michael: Just playing music- to write your own songs. Because there really was no blueprint for playing hardcore punk rock.

Ian: Right. And that’s exactly the point of it. To me, punk was, the idea was, that the audience was there for the new idea. And that was the difference. Actually, the problem today is that, the way things are structured now, the people who have access to stages either have to be known or they have to have some referential thing- they have to be known from somewhere or have done something OR they play a certain kind of genre, because obviously, audiences are clientele and for clubs to bring you in, you have to have an audience. New ideas don’t have audiences because they haven’t been thought of yet.

But what I love about punk and why I think punk is still alive is that there is an audience—it’s small—that’s just like, “Okay, what do you got? We’re here for the new idea.” So in a way, the blueprint was that there was no blueprint. And unfortunately, the longer you’ve been involved, you can see, somebody comes up with an idea and then people just start doing that thing. And it becomes calcified in a way, or it becomes an orthodoxy. But then you just have to keep moving, keep going, keep the new idea, keep it coming.

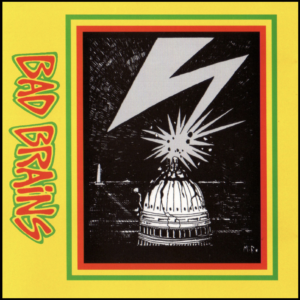

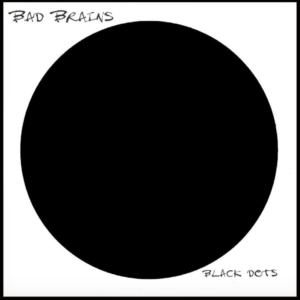

It’s interesting. I was just talking about that ROIR tape today with these guys at my kid’s school. And I was talking about how for me, the ROIR tape was weird. I grew up with [Bad Brains] here, and Black Dots, that era, that stuff was like the greatest recording ever. And I remember just thinking, that ROIR thing is just so weirdly fast. They were playing super fast and it sounds so shitty, but I said to the guys today–I said to those dads– this tape was a fucking game-changer. This is the tape that changed people’s minds. People’s minds were exploded. The Black Dots tape was like the Dove tape. The only people who had the Black Dots tape were like me, Henry [Rollins], and eighteen other people around town. It didn’t get out. Not ‘til later.

Like the Dove thing. That is so obscure. The fact that you have the Dove tape, is so bizarre to me. Like the Black Dots. Way more people had Black Dots than Dove. I think the ROIR thing, that’s where most people first encountered the Bad Brains. And it’s kind of an incredible recording. But from my brain, from my perspective, it was sort of like, “What have they done to their incredible sound?” It’s alright. I can listen to it now and really respect it. And I’m happy to hear you talk about it because I was just telling those guys that this tape was like a bomb that exploded all over the place. It was pretty incredible.

Sarah: So it was just that the ROIR tape had gotten distributed further than anything else had?

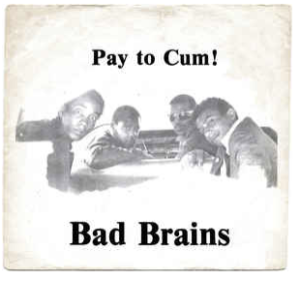

Ian: The only thing they had put out prior to the ROIR tape was the Pay to Cum single. They put out 1,000, and that was on their own label, Bad Brains [Records]. Henry and I lent them some of the money to do it. That was before Dischord. So you’re talking about hard-earned pet shop money. You know, [meekly], “Here’s 50 bucks.” [laughter] But then they went to New York and they did this ROIR cassette.

I used to be so angry. People would talk about Husker Du, and they’d say, “Fastest band in America!” We’re like, ‘Really? Because we’re from DC and we have the Bad Brains.” And then I thought, “I want to hear these guys.” And I heard Land Speed Record. And I thought, “Yeah, okay. They’ve got a fast tempo but they’re sloppy.” The Bad Brains were precise. So I just remember thinking, “A fie on Husker Du!” [laughter]

Michael: So there was no place in Rochester at the time to find this music. Very few people were into it. I was flipping around on the radio dial—someone had mentioned that some of the college radio stations play some cool stuff. And the Rochester Institute of Technology, WITR—it was like a life-changing moment—they had this show, it was called “The Friday Night Filet,” where a deejay, at 11:30, would play everything by one artist. And there was a commercial for the Minutemen. And I was like, “What the fuck is this?” So I taped that.

Michael: So there was no place in Rochester at the time to find this music. Very few people were into it. I was flipping around on the radio dial—someone had mentioned that some of the college radio stations play some cool stuff. And the Rochester Institute of Technology, WITR—it was like a life-changing moment—they had this show, it was called “The Friday Night Filet,” where a deejay, at 11:30, would play everything by one artist. And there was a commercial for the Minutemen. And I was like, “What the fuck is this?” So I taped that.

Ian: Was it Double Nickels or something?

Michael: It was before Double Nickels.

Ian: I think Project Mersh was out by then.

Michael: The radio show played everything leading up to Double Nickels on the Dime, which was due out soon. I rode my bicycle up to the record store and bugged them every Tuesday for a few months until the singles came out.

Photo of Record Archive from recordarchive.com

Ian: What was the name of the shop up there?

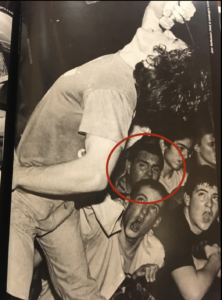

Michael: The one I went to was Record Archive on Mount Hope Avenue. That’s where I bought Double Nickels when it came out. That radio station started a punk show. And one of the deejays was from DC. His name was Jon Hull. There’s a picture of him in Banned in DC in a crowd shot. It’s a Jim Saah photo of Void playing. He’s one of the people in the audience. He brought his record collection with him. One of the other deejays was from the New England scene- a lot of Connecticut and Boston hardcore in there. So, I started hearing stuff that you couldn’t find in stores. So I started taping the radio and sometimes sitting down and playing guitar along with these recordings. I took some guitar lessons.

Jon Hull circled in photo of Void by Jim Saah from Banned in DC: Photos and Anecdotes from the DC Punk Underground (79-85) by Connolly, Clague, and Cheslow

Ian: You’d been playing for seven years when you wrote that letter.

Michael: Yeah!

Ian: You said that in the letter. He says there, “I’ve been playing for seven years.” You got that in there. “I’ve been playing for seven years.” [laughter]

Michael: This is so sweet that you—I can remember writing this letter.

Ian: Before you guys go, I’ll show you the archive room.

Sarah: Yeah, how would you have dug that up, out of all the letters that you receive?

Ian: You will find out. I’ve been doing my work here! I’ve been working hard. You know how I found it? I typed in “Michael” into a database—

Michael and Sarah: WHOAH!

Ian: –that led me right to the folder and box which it’s in. We’ve been working for the last eight years in archives, and I have 35 years of correspondence. And I figured when I saw that he had the tape, I was like, “I bet you…” The letters that got tossed are usually like, “Send me a catalog.” So anyone that actually engaged—was engaging—I’d probably hang on to that thing.

Then for years and years and years, I kept boxes of mail. And they’re literally in the eaves. The eaves of this house, I lined them with pressboard cedar just to keep the bugs out. And there were the boxes. And then about eight or nine years ago I started working with different people on archiving projects. We first worked on the audio stuff, then we organized the posters, and we started working on the correspondence about three years ago.

[Ian fields a telephone call.]…Ian: So how are we doing on this thing?Sarah: We got Michael to the ROIR tape. Now we need to get Michael to the letter and the tape.

Michael: Right! I can remember vividly writing this letter. But what I can’t remember is what on earth would give me the gumption to write to you. Because even now I feel very mindful of other people’s time. Like, “I don’t want to bug them.” I know people are busy.

Ian: I think the discourse was open. I think people wrote to each other all the time. I actually don’t think probably at that time—I wouldn’t say you weren’t mindful. But it wouldn’t have been mindless to write somebody. I think that people think that now. I find it shocking that with all the development in communication, that people find it so difficult to write. Or talk. Or respond. I find it amazing. Everyone seems to be so busy, but what they’re really busy at is looking at things. I don’t know what else to say about it. It just seems strange.

Ian explaining

Look at that. You sat down and wrote a three-page letter. Part of it—you’re pleading your case. You want this tape bad. And this is what you have to go through to get it. What I find startling about that—I don’t know if you looked at the whole letter—but at the end of the letter you say, “Yeah, we made a tape. I’d love to send you one but I’m poor. If you want to buy one, it’s $3.” [laughter] Meanwhile, you’re asking me to fucking make YOU a tape! [laughter] You said, “I’m poor, but if you want to buy one, it’s three dollars.” I mean, why didn’t you just send me a tape? And then trade it? It’s a little startling!

Michael: Amazing.

Ian: But I think probably—who knows what you were thinking. One thing about punk in general and me specifically is that—and it’s still the case—I’m accessible. And people felt comfortable getting in touch with me. I’m still in the phone book, but people always say, “Man, I’ve been through so much to try to figure out how to find you.” It’s so weird.

So I think that I’ve always been accessible.

Sarah: Yeah, has this changed over time?

Ian: No!

Sarah: Because it’s one thing when Michael’s writing you this letter, and it’s the late 80s–

Ian: it’s just the work. It’s just my work. It’s what I do. People contact me one way or the other and I respond, one way or the other. I think there’s a couple things at play here.

There’s a different sense of what the value of recordings are now. I’d be much more loathe to send a tape now because someone would just post it. And that’s a big problem. I’ve actually made little demoes. Amy and Joe and I have been working on something, and a friend of mine said, “Oh, I’d love to get a copy.” And I said, “Yeah I’m not going to give you a copy.” “Don’t you trust me?” “I trust you. I don’t trust the person that you give a copy to.” And once it goes, it goes. You can’t take it back. It’s like the genie is out of the bottle. When you showed me I sent this, I was like, “O my god, that could be out there.”

I think at this point in time, a band like Dove, they recorded—I would say it wasn’t a great session. It was interesting. And the results—I would say it’s the best they did. I think the later stuff they even lost the plot more. But it wasn’t really something we could release. And people don’t understand, at Dischord, we were broke. Broke broke! People say, “Why didn’t you put this out?” Because we didn’t have money! We were hand to mouth. We put out a record. Then we had to wait to sell them to make enough money to put out the next record. I couldn’t put it out. But I liked it. I thought it was kind of a cool recording.

Click to view a facebook post from “Brian D. Horrorwitz:” September 17, 1983 footage of Dove playing a house party

So when someone actually expresses an interest in something that’s that obscure, I’m like, “Thank you for asking. Here’s a copy.” I made a lot of tapes for people. Mostly because, speaking from my own work—people say, “How do you feel about file sharing?” Every song I ever wrote, I wrote to be heard. So, if no one wants to pay for it, that’s fine. But to know that somebody wants to hear it, that’s the point. It’s not the dollar. It was always to be heard.

And I figured, “Well, the letter’s sincere.” I could tell he’s not some scummy bootleg guy. He’s genuinely knowledgeable. He’s clearly a student of music and specifically a DC fan. You reference Marginal Man and Double O and all this shit, so I knew that you knew. So I’m happy to share.

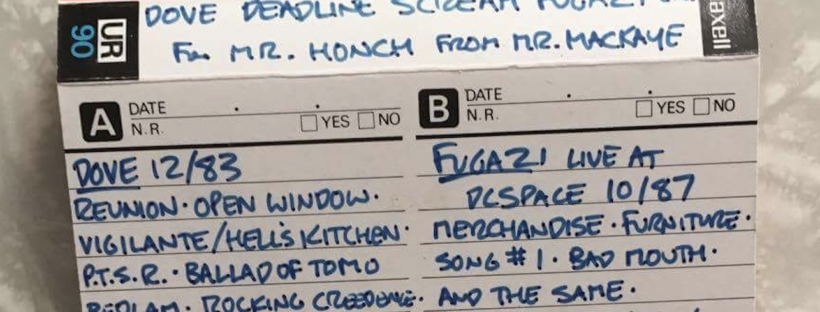

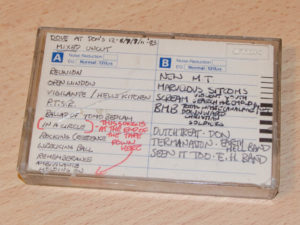

It’s a good tape, too. What did I give you? I gave you Dove, Deadline.

Tape insert, photo courtesy of Michael Honch

Michael: That was there for my health and improvement.

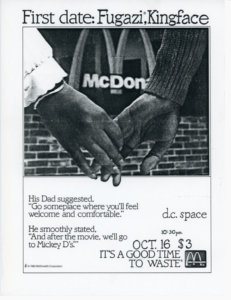

Fugazi show flyer from October 16, 1987 show at d.c. space.

Click to download show from the Fugazi Live Series on Dischord.com

Ian: This is the second tape, right? It’s the 8 or 9 song tape. And then I put Fugazi on there! So you’re talking about that [in the letter], “-your new project.” And I’m like, “Well there it is!”

So you heard this. This would have been our fourth show, probably.

Press Mob were good. I like that song Sundays. That’s on the DC Rox comp.

Yeah, I love this song P.T.S.R. That’s a good song. That was written by Toni Young. Of Red C.

Michael: The bass player. Yeah.

Ian: Peer Pressure also did a version of that song. It’s a good jam. Toni was a good person. She shuffled off in ’86. So it goes.

So I just wanted to share music. I was happy to do it. People sent me stuff, too. So I’d occasionally get tapes from people.

I remember going across the country. I saw the Butthole Surfers for the first time in 1981. I saw them in L.A. Maybe ‘82. It was before they had a regular drummer. They were just a four-piece. They were so fucking weird. We saw them in L.A. and then we went to Austin. And we’re hanging out with the Big Boys. I said, “What do you know about the Buttholes?” And they were like, “We got these tapes.” I was just making tapes!

Actually, I’ve been typing up my ’84 journals, and I write that Henry was visiting, but spent all of his time sitting upstairs making tapes. ‘Cause that’s all we did. You’d go to someone’s house, you’d make tapes because you were getting back on the road. You’d need to have tapes. So he was just copying tapes. And that’s what we did. Everyone had stacks of tape decks and were making tapes. That was the discourse.

Michael: Now that brings back really good memories, too, of all the tapes from my bands—I’d go over to my parents’ house and use their dubbing deck. And we’d get orders from Maximum Rock N Roll and be making copies of them one at a time. But also- that radio station- WITR where I first heard punk rock- my first band, we recorded ourselves with a boom box and then showed up at the radio station with it. They were like, “Wait, there’s a punk band in this town?” And they played it over the air! That was when [I thought,] “I think I found where I can grow here.”

Michael Honch, 1987, Rochester, NY

My first show was opening for Beefeater. That was the first time I really had to fight hard with my folks because I was a sophomore in high school at a bar.

Sarah: You had to fight [your parents] just to get there to play the show?

Michael: Yes. I was a little terrified. That was an intimidating band to play with. But Fred Smith [guitarist of Beefeater] came up to me before the show. I’m talking to him. And I said that this is my first show. And he said, “Show ‘em what you got!” And then my vivid memory of that is that I had this ridiculous solid state Marshall amp. It was like a mini stack. And he was crouched behind it, with his fist in the air, screaming “Yeah!”

Ian: That was your first gig!? Your first gig playing with them, or your first gig, period? You didn’t play a party before that?

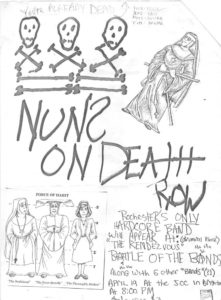

Flyer for the first show Michael played, in Nuns on Death Row

Michael: The only show that I’d ever played before that was a battle of the bands at the local Jewish community center.

I had missed them the first time they played in Rochester because I was grounded. And they played with Dag Nasty at RIT with Shawn [Brown] still in the band.

Beefeater – “Need a Job” with Fred Smith solo

Sarah: …To circle back, when was the last time someone has asked you to make a tape for them?

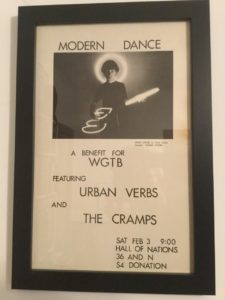

Ian: A tape? Today I was talking to a guy—this will give you an idea of who I am. I was just over at this My Organic Market over here. And there’s a kid who works there who I see around, and he’s a nice guy. And he was wearing a Cramps shirt. I said, “Hey, that’s the first band I ever saw!” That’s the poster for the first show I ever saw right there [gestures to wall] that Cramps show.

Cramps poster at Dischord house

Sarah: Wow!

Ian: February 3rd, 1979. So then I said to him, “That’s the first band I ever saw. 1979.” And he’s like, “No way!” He’s probably 19 or something. And I said, “I think I have some live stuff. I’ll make you some copies of it.” So I saw him today, and I was like, “What do you want by the way? I don’t know what medium you want.” I was thinking I’d make him a cd or something. He said, “Anything’s fine.” I could easily make a cd for him. Or I could make a thumb drive. I can’t make vinyl. And I’m not really inclined to make a cassette. It’s a pain in the ass.

BUT, to answer your question, there’s a Japanese guy who works at the market at 17th and U. And he is a very enthusiastic guy, and he loves ska. He loves ska so much. He’s a trombone player. I’ve seen him in his band. So we were talking about it, and I was like, “You only listen to ska?” And he’s like, “Oh yeah, only ska.” And he goes, “Maybe a little reggae.” I said, “What about rock steady?” And he says, “Oh yeah.” I said, “Do you want some cds?” He said, “No, cassettes only!” So I have these cds, which I think I made from cassette years ago. This guy from New York just sent me these compilations. So I made cds. Or maybe he made me cds of his cassettes. I can’t remember now. He sent me so many things over the years. So I took the cds and I made this kid three cassettes of rock steady. That was maybe three weeks ago.

Sarah: Wow!

Ian: You see these boxes behind [Michael]? Those are filled with cds. I have literally thousands and thousands of pieces of plastic that have music on them. And they’re inert unless they do something. So when someone says to me, “I like this.” I’m like, oh shit, let me break this out of its fucking tomb. Give it some reason–

Michael sitting in front of boxes of cds

Even the letter! Honestly, I’ve spent so much money and so much time on this fucking project upstairs. And to actually have a reason—like, “Oh, there you go!” Just for the moment where you guys were like, “Noooo!” That’s the pay off, right?

That’s the fucking point! Why else did I keep it? What reason on Earth would I keep it if it weren’t to show you that letter? What’s the point? What’s the point of it?

That’s why I do everything I do. It’s just potential. You just do the work. Then someday it shows up. The reason you did it will show up. I don’t know. That’s how I operate. That’s how I’ve always operated. I just do my work, do what’s in front of me.

Like this morning, I was like, “Oh yeah, I’ll look for that letter.”

So yes, I think the idea of spreading the word. I’m not a formatist. Cassettes. There’s an aspect of cassettes which I think is really valuable. First of all, they’re hardy. Let me show you something.

I was typing up my 1984 journal. And in that journal I came across a thing where I spent an evening at the Connollys’ house. I had just typed about it. And I was going through trying to look at some tapes today for this thing. And I came across this tape. And it says [reads the cassette label], “Ian, Anna, and I arguing March 7, 1984” Oh shit. That is incredible. That she had this tape. And I have the tape.

The deal with tape is, the tape itself is very, very hardy. What is not hardy is the mechanism.

[Ian demonstrates to Michael and me his tape transplant method.]

Felt pad

So you can see in here there’s a felt. And the felts on these things, typically, they’ll dry out or they’ll fall off. And the point of the felt is to apply pressure on the back of the tape. Because when you push play, it pushes the head into the tape, and you want to have a nice firm contact. When you have this felt drop off, there’s no firm contact, so you get the [imitates muffled voices]. So, what you do then is—this one unfortunately is not a screw tape, so I actually was just in the process- whilst waiting for you to show up- I was in the process of using a screwdriver. I started just splitting the tape open. Which I will do. I will split this tape open.

Then, these are C-Zeros, there’s no tape on them. These are screws. So, you take the top off. Take this little zero tape. There’s nothing on there. See? And you just drop these hubs in. Boom.

C-Zero photo from www.duplication.ca

They fit perfectly. Because when they made cassettes, there was an argument about what the format would be. You know how there’s beta and VHS and HD and Blu-Ray, all that kind of crap? Well cassettes had the same kind of thing, but the manufacturing people decided to agree on a standardized format.

So this is Cynthia [Connolly]’s mom’s tape when she was in law school in the mid-70s. This is a 40-year old tape. This will fit perfectly into this [C-Zero cassette]. Uniform.

Sarah: That is pretty amazing.

Ian: Upstairs I can actually give you an example of the difference it will make. But you can see, that felt is fine. The spring is still there. So when I do that, it will make the clarity of this mind-blowing.

So cassettes. There’s a practical component to them. They’re very hardy. They’re also democratic. Everybody can do it. A band like [Michael’s late-80s band] Hunger Artist could record a practice and take it over there. But you couldn’t make a record. Making a record, that was some next-level shit. Also, making a record requires you to make a financial commitment and also a commitment into creating multiple pieces of plastic. You don’t make five records. You’re going to make 500 or 5,000. And if you make 1,000, that’s a lot of records. There’s a lot of people in this world who have under their beds boxes of records they couldn’t sell. Because you had to make 1,000 or 500 at the minimum. That’s the way those pressing plants used to be. It’s not worth the origination because there’s a whole series of steps leading up to the creation of the pressing itself. You have to master it. You have to make plates. You have to make stampers. There’s all this stuff that went into that. So, it wouldn’t make any sense to only do a small run. You have to kind of speculate, like “Well, we could do 1,000, and then it would cost x amount per record.”

Cassettes are one to one. That’s the populist way. Here’s a tape. And you could just make the tape. So it was the people’s format.

And it’s finite, which is nice. The problem with digital is that it’s not finite. It never ends. Online or digitally, you could have something that’s 100 hours long. But cassettes are like C-30, C-60, C-90. C-120, but you’re starting to stretch it out. They are finite.

And they have sides, which is also important. The distinction between vinyl and cds was that with vinyl you had two 15 to 20 minute sides, which meant that– you might listen to side 2, you might listen to side 1. So when you sequence an album, you would always think about what leads off side 2. Because that’s also significant. It’s the first song. So you would think about the sequencing.

Side twos

CDs have one side, and they’re 70 minutes long. And people don’t listen to music for 70 minutes. They listen to music for about 15-20 minutes, and then it becomes background. So sequencing for a CD was just front-loaded. And then they put a bunch of drivel at the end, basically. Vinyl and cassettes had sides, so you knew, “O yeah, turn it over.” That’s that side. It was an interesting format. And it was easy to do.

It’s generational, which is a problem. Like when you make copies of something- a copy of a copy of a copy. It just starts to sound shitty. That’s why digital kicked ass on that front. I mean for bootlegs, God, the digital format was amazing. I mean, I have hundreds of Beatles and Hendrix bootlegs that have come through the internet or digital, and they’re incredible quality. Cassette bootlegs just sound shitty because they’re copies of copies of copies. Vinyl bootlegs sound shitty because the people who would press them had to be a back-alley operation. You weren’t going to get good pressings.

Sarah: Yes, I have some of that. Before I understood any of that, I bought some Clash bootlegs from Phantasmagoria [Records].

Ian: Yeah, and then the thing about those is that those were pressed from probably cassette recordings that had been copied and copied and copied. So there’s an issue there.

Ian with Dove masters

For instance, what [Michael] has there, the tape I sent him, is a copy of a copy of the master. So, when we did that session, we mixed it, and then Don [Zientara] had a tape deck in the room, and he’d say, “How many tapes do you want?” And here’s the thing about how many tapes you want. Let’s say the tape is 30 minutes long. This is probably 30 minutes long or something like that. If you have a 30-minute tape, and Don says, “How many tapes do you want?” well, people who are in the band all want first-generation tapes. So there’s four people in the band. Well that’s four times 30. So that’s two hours. And you’re paying Don per hour. So you’re paying for the tape, and you’re paying for the time. So you’re never going to make a tape and then say, “I’ll just give you a copy of our tape.” People don’t want that. Everybody wanted a first-generation copy.

So the Dove tape I have upstairs would have come right from the deck, from Don’s, and then I would have made a copy from that. The other thing about cassettes is that every time you play a tape, you lose a little something. So that’s the other issue. They’re hardy. But most of us had shitty decks. And the bias would be bad.

Ian’s Dove tape

Here’s the thing about this tape [of Cynthia, Anna, and I arguing.] This is a shitty recording on a shitty tape deck. You can tell how shitty it is because there’s no screws in it already, so you know it’s just going to be a shitty tape. It’s old. But the thing about it that makes it really priceless is that it’s the only one that exists in the world. It’s the only existing recording of us having an argument on March 7, 1984.

So taking that over the alternative, which is nothing the fuck at all, it’s pretty valuable. So, that’s documentation. That’s the idea.

So that [Dove] tape, it probably didn’t sound that bad.

Michael: It sounded great to my ears.

Ian: But tapes do, they start to get wonky. Good luck writing all this up. I don’t know what you’re gonna write about but—

Sarah: [laughter] What was Dischord like around the time that this tape was made?

Ian: Let’s see. Fugazi would be practicing here at that point. And Happy-Go-Licky was still practicing here. I think 3 were around. Everybody practiced downstairs. So we had this full-on constant—the whole house would be like bbbbwwwwwwrrr. The bands were practicing in the basement while people worked on the label upstairs.

[Ian shows photo.]

Shipping office at Dischord house, circa 1990

Sarah: Well it looks very organized.

Ian: Pretty organized. Always been pretty organized. But Dischord was thriving. I’ve been typing up this ‘84 journal, and the amount of people socializing and the amount of people coming and going. Everyday, people are showing up. My brother, Chris Bald—and then The Meat Puppets and Black Flag and everyone just constantly coming through. Many of them practiced in the basement. It’s one of my great regrets that I didn’t keep a guest book. I actually don’t even remember all the people that have stayed here. And I remember thinking about three years in- I should have kept a guest book. And then at that point- ah well. I’m not going to start now. But I probably should have.

But the amount of circulation was fascinating. People were just coming and going, coming and going.

These days, it is so rare. People will come here on a formal thing now. Like, this is a formal arrangement. We took weeks of cc:ing each other to fucking have a sit-down. But the sort of spontaneous, the sort of “I was just in the neighborhood and thought I’d stop by,” that almost never happens anymore.

Sarah: Really? I would think it would happen more because with the Internet there would be more people aware—

Ian: More people show up to take their picture on the porch. That’s different. That’s not the same thing. That’s just people wanting to take a picture because it’s like sightseeing. I’m talking about tribes forming and people making the connection and appearing.

I have upstairs a lot of the tapes from the answering machines.

Sarah: Whoah, you saved the tapes from the answering machines?

Ian: Right, ‘cause I would use cassettes, and I would just let it run. And then occasionally, I would pop it out and put a fresh one in and throw it in a box. Just to have. So I had, like, 20 of them. And I was listening to one of the first ones we had. Some of the tapes actually have messages from people where it’s like, ‘I would keep that!” But in most cases, it’s just random stuff. I’ll play you some.

But one of the tapes I have—at that time, on that machine, the phone would ring and the answering machine would go off. Remember how people would say, “Hey it’s me. I’m here. Pick up! Pick up!” The fancy machines would cut off at that point. But the old machines just kept running. So you had to remember to turn off the machine. So, I have a tape where Amy Pickering is calling looking for me. And at this time, we had five phone lines in this one house. So Amy calls the house line. And she’s like, “Hey! Ian are you there? Ian are you there? Are you there? Are you there?” And then Mark Sullivan picks up, because he’s living upstairs at the time, and he’s like, “Hey it’s Mark. Is Ian there?” “No, he went out.” “Shit.” “How you doing, girl?” [sigh] “Really? What’s going on?” “Kind of a shitty day.” “What’s been going on?” And then they start talking. I was thinking about it. That’s a spontaneous conversation. And that has been terminated. If I call you, I’m never gonna get [your husband] Chris. He’s not answering that fucking [cell] phone.

Sarah: No.

Ian: If I call you [on the cell phone], I’m not gonna talk to your kids. That is a really interesting social change.

Sarah: Definitely.

Ian: Because when you think about calling group houses, or even calling your friend and talking to their parents. There’s real transference there. And also, there’s an intimacy that develops. It’s how you become friends with people. You call a group house and then someone else answers the phone and you’re in a conversation. You’re like, “Hey let’s have a cup of tea sometime!” It’s very interesting. I’m not a Luddite. I’m not against progress or whatever you want to call it. It’s just something to think about, the effect it has on the interactions. It’s like- so much online community, in isolation. It’s fucked up.

Sarah: Yeah, I think a lot of the people you think you’re in a community with online, you wouldn’t really want to hang out with.

Ian: Right. That’s the stuff I’ve been thinking about. Among the millions of other things I’ve been thinking about, that’s something I’ve been thinking about.

Sarah: Are you going to do anything about these ideas?

Ian: I just did!

Sarah: [laughter] Well I guess I do wonder- is there something to do about this? I mean, you conduct your own life in a certain way. I guess that’s step one.

Ian: First of all, I don’t have any social media at all. I get it. I just can’t get involved. It’s too much. The media component of social media is toxic. I feel for people who are being traumatized by the perpetual weirdness coming out of the White House and Capitol. Take it out of your pocket! You don’t need the needle over and over and over. Goddamn. I don’t see the benefit.

A friend was saying, “The problem with the newspaper is that you can’t update it.” The paper-paper doesn’t update. And I was like, “Yeah, that’s not a problem. That’s okay.” He is traumatized by the Twitter. I’m just like- stop. What’s the point of it?

Shitty things have always been happening always in the world at all times. While we’re talking right now, something horrible has happened to somebody somewhere. And it’s not within our control. It’s not at our beckoning. We didn’t do it.

Why did we have to learn about a car crash a mile away from here and not about one that happened in Omaha? Why is a car crash where one person was killed on Key Bridge more important than a car crash where eight people are killed in Des Moines? What’s the difference? The curation of news and the way information is given to us is really to make us feel terrible, by and large.

When this motherfucker got into office and all this shit was going on, I said to people, alright, they got the House. They got the Senate. They got the White House. Don’t give them your joy. Don’t fucking give up on joy. If you don’t have joy, then fuck it, what’s the point? They can’t take your joy. So I feel strongly that people should stop engaging in feeling terrified. Fuck fear! Don’t be scared. These are jerks. They’ve always been jerks. Always. These are more demonstrative jerks. But, it’s gonna pass. It always passes.

A friend once said to me, “Bigotry always falls on the wrong side of history.” You just gotta wait it out. And it didn’t start with them! They’re the end of this particular strain. The same friend also once told me—you ever hear about this thing called extinction bursts?

Sarah: No.

Ian: It’s a great term. An extinction burst is the burst of energy right at the end of something’s existence. When animals die and then all of a sudden, rrrrrrvvvvrr, they do that thing. Or another great example is when there’s a bully, and you tell your kid, “Just walk away! Don’t give them that power!” But when you walk away, the bully attacks. The bully does that because he or she knows that their power is at the end. It’s an extinction burst.

This is an extinction burst. This is what we’re seeing. It’s the end of the Vietnam-era, White men problem. And it’s a bummer. And I’m sorry we have to deal with it. But that’s the way it goes. It’s not my doing!

Ian and teapot

I’m also the guy that on September 11th, I was sitting here and Amy Pickering was at the office across the street, and she called me and said, “Do you see what’s going on?” I said, “No.” “Turn on the tv.” Then I saw, yeah, someone crashed a plane. How terrible! And then I saw the other plane come in, and “Oh, this is not an accident. Oh shit! Alright.” I turned the tv off. What can I do? I’m just fucking sitting here, right? And then, a call: “They just crashed the Pentagon!” “Really?” I walked up to the top of the street to look and see the black smoke. I’m like, “Wow! Okay.”

Then I come back and people are calling, like, “What are we gonna do? What are we gonna do? What are we gonna do?” And I just said, “I’m not gonna do anything.” “I’m gonna do my work.” And people are like, “Should we go? Should we drive somewhere?” “Where? Where would we drive?” People are like, “There’s still eight planes out there!” Okay. We had zero control over this situation! I had nothing to do with whatever led to it. I had nothing to do with the actual event of it. So I thought, “Well fuck it.” I had a bed in the back room that summer, and I was lying downstairs, and I saw the trees, and I saw the birds in the trees, and I thought, “They don’t give a fuck. The birds in the trees don’t give a fuck about this. And I’m on their side. I’m not going to get caught up in the brutality of human folly.”

I don’t know why humans do this shit. They’ve been doing it forever. Just some of them. Not most of them. But enough to terrify the rest of us, I guess. I’m with the trees and the birds. That’s life. That’s the real deal.

So then everything was fucked up. They had closed the bridges. We couldn’t go out. We were stranded here. And I was sitting here by myself, and I was like, “Fuck. I know. I’ll answer the mail.” So I get a big box of mail, and I sat here, and I was just writing, and I was like, “Oh! I should date it September 10th, because I don’t want people to think I’m insane, right?” And also because I saw it as a vote for the future. Because that’s the thing about letters. Like when you wrote that letter, it was one day, but when you sent it to me, it would be a different day. So you believed in the future.

Michael: Yeah.

Ian: And that’s how I thought. I thought, “I’m writing letters because I believe in the future.” Right? Because I knew when I wrote that letter, they’re gonna get the letter in two days.

And about four or five months ago, I got an email from a guy, and he said, “You know, I was just going through my mail. I have a box of old keepsakes. And I found a card from you. And it’s dated September 11th, 2001.”

Sarah: [laughter] Oh no.

Ian: And he’s like, “Were you really answering mail on September 11th?” I’m like, “Shit!”

I wrote back and said, “I can’t believe you got that!” But that’s the thing- I didn’t watch television [that day]. What’s the point? It’s incomprehensible, right? The brutality. It would never make sense why people would do that. I don’t want to see people jumping out of buildings! I don’t want to look at that kind of shit. The only thing you can achieve, really, by looking at it is becoming numb to it. And I’m not interested in that. So I was like, “I’m not gonna watch it.” So I may have been one of the five people in America who didn’t watch it all day. And therefore, I was like, “Okay. Here we are.”

I’m for joy! That’s my gig. I want to be well. I want love. That’s it.

When Ian stepped out of the room, Michael had this to offer about the effect that receiving this tape from Ian had on him.

Michael mid-thought

Michael: I look at that letter there and what he said about [what I wrote], “I’m really poor. It’s three dollars.” I’m mortified seeing that but at the same time I think—one of the things that impressed me about this so much was the generosity of it, without expecting anything in return, except to listen. But it’s something that I carry with me. It’s one of those ripple effects. I think about ways in which this changed how I think about sharing work with other people—that it’s possible to communicate with people in ways in which there wasn’t an economy to it. There wasn’t a quid pro quo. It was really, really encouraging.

Michael was born and raised in Rochester, NY. He played guitar in Nuns on Death Row (1985-1986), one of Rochester’s first hardcore punk bands. He also played guitar in Hunger Artist (1987-1989) and Powerline (1990-1991) with Zach Barocas, who would go on to drum with Jawbox.

Michael quit playing music in the early ‘90s, moved to the DC area in 1994, and earned an MFA in creative writing from the University of Maryland at College Park, where he also taught as an adjunct. He ended up working in the used book business for the next 20 plus years.

Michael bought his first bass guitar in 2008 and joined ex-Circus Lupus guitarist Chris Hamley and ex-Crownhate Ruin drummer Vin Novara in 2011 to form Alarms & Controls. The three made the “Reanimus Cataract” single (Mud Memory 007/Dischord 174.5) and the “Clovis Points” LP (Lovitt 75.5/Dischord 181.5). Michael was also a member of the two-bass duo Argos; they collaborated with BELLS≥ on a track from their “Solutions, Silence, or Affirmations” LP, which reunited him with Zach. Michael currently plays bass in Numbers Station, a 2-bass instrumental trio. https://numbersstationdc.bandcamp.com/releases

Michael went back to grad school and earned a Library Science degree from UMD in 2015. He is now a librarian at the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

His favorite Dischord release is still Faith/Void.

Michael

Ian MacKaye was born and raised in Washington, DC. He is the cofounder of Dischord Records and has been the member of myriad bands including Minor Threat and Fugazi. His most recent band played its first show November 11, 2018; it is a collaboration with Amy Farina and Joe Lally. In the photograph below, Ian is holding a copy of the first mix tape he ever made.

Ian